Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Bitterness and Food Rejection

step 1

change the question

Greene et al’s question:

‘We developed this theory in response to a long-standing philosophical puzzle known as the trolley problem’

(Greene, 2015, p. 203; see Greene, 2023)

problem: there are confounds.

Which factors influence responses to dilemmas?

- whether an agent is part of the danger or a bystander;

- whether an action involves forceful contact with a victim;

- whether an action targets an object or the victim;

- how the victim is described (Waldmann et al., 2012).

- whether there are irrelevant alternatives (Wiegmann, Horvath, & Meyer, 2020);

- order of presentation (Schwitzgebel & Cushman, 2015);

‘almost all these confounding factors influence judgments, along with a number of others’

(Waldmann et al., 2012, pp. 288–90).

‘almost all these confounding factors influence judgments, along with a number of others [...] The research suggests that various moral and nonmoral factors interact in the generation of moral judgments about dilemmas’

(Waldmann et al., 2012, pp. 288–90).

alternative question

What is the relation between

ethical attitudes

and

the behaviours which they sometimes but not always control?

step 2

distinguish ethical abilities

Greene et al’s assumption:

‘morality is a suite of cognitive mechanisms that enable otherwise selfish individuals to reap the benefits of cooperation.’

(Greene, 2015, p. 198)

ethical abilities

- care

- cooperation (Boyd & Richerson, 2022)

- inequality aversion (Brosnan & Waal, 2014)

- balance authority vs autonomy (Wengrow & Graeber, 2018)

- discern impurity (Chakroff, Russell, Piazza, & Young, 2017)

- ...

step 3

find a non-ethical model

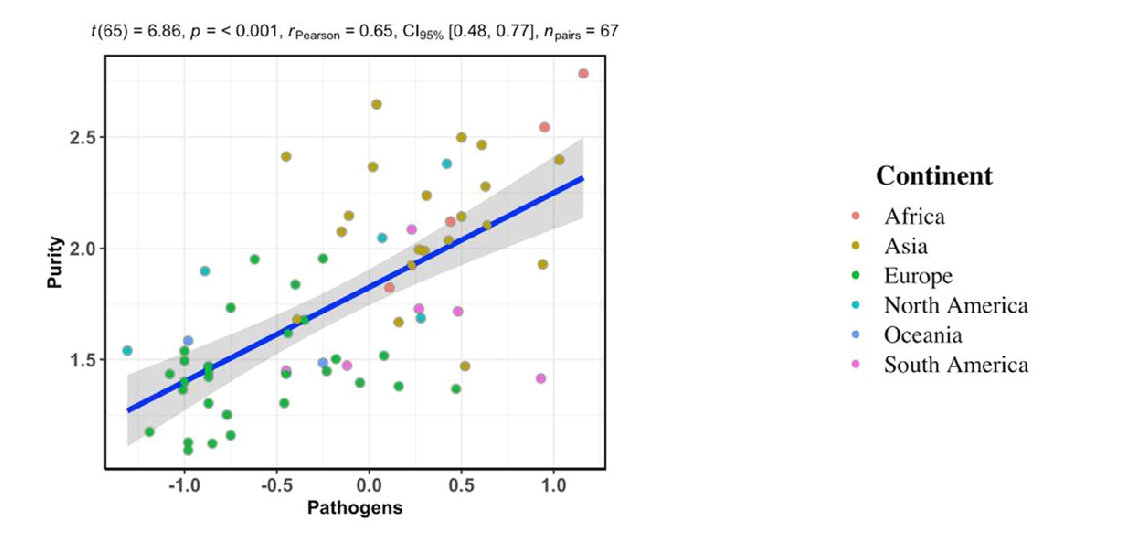

Atari et al. (2022, p. figure 3 (part))

food-rejection behaviours

problem: need nutrients / risk poisons

slow: toxicity judgements

fast: aversion to bitterness

purity-related behaviours

problem: need play / risk pathogens

slow: purity judgements

fast: disgust

disanalogy: bitterness vs disgust

objection: it’s not intrinsically ethical

‘When it comes to morality, the most basic issue concerns our capacity for normative guidance: our ability to be motivated by norms of behavior ...’

(FitzPatrick, 2021)

step 4

borrow an idea about normativity

minimal norm

- a pattern of behaviour

which exists in part because of others’ responses to behaviors which conform to, or violate, the pattern;

where these responses have the purpose of upholding conformity to the pattern.

objection (recap): disgust-driven behaviours are not intrinsically ethical

reply: disgust can underpin purity-related minimal norms independently of normative attitudes.

purity

slow process

driven by purity judgements

fast process

disgust underpins purity-related minimal norms

conclusion

What is the relation between

ethical attitudes and

the behaviours which they sometimes but not always control?

thesis:

(i) disgust can can underpin purity-related minimal norms independently of normative attitudes; and

(ii) this is one reason why ethical decoupling occurs.

predictions (~):

(i) learned disgust can give rise to minimal norms; and

(ii) the minimal norms can outlive changes in ethical attitude.

There are behaviours which are sometimes, but not always, controlled by ethical attitudes.

terminology: ethical decoupling

What is the relation between

ethical attitudes

and

the behaviours which they sometimes but not always control?

challenge: characterise the processes, and the behaviours

limits

(i) only one domain (purity); and

(ii) the thesis merely restate some old ideas.

| Greene et al | Disgust + Minimal Norms | |

| characterises cognitive aspect of processes | ✓ | ~ |

| characterises what processes compute | ✓ | ~ |

| the processes are distinctively ethical | ✓ | ✓ |

| theoretically motivated | ~ | ✓ |

| generates predictions | ✓ | ~ |

| predictions confirmed | 𐄂 | ?? |