Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

But One We Can Work Around

Part 1: characterisations of mental states generally

Part 2: characterisations of particular attitudes

Start with

Perner’s Strategy

theory

(ensures shared understanding)

‘representation involves a representational medium that stands in a representing relation to its representational content.’

(Perner, 1991, p. 40)

conjecture: link to mindreading

diverse desire -> representational relation to situations

false belief -> representational relation to representations (metarepresentation)

predictions

‘developmental levels can be theoretically tied in with my analysis of the concept of representation’

(Perner, 1991, p. 284)

alternative?: ‘Beliefs [...] represent nothing.’

(Davidson, 2001, p. 46)

Perner’s Paradox

1. Ancient philosophers were deeply puzzled about the possibility of speaking and thinking falsely.

2. Ancient philosophers could have passed false belief tasks.

3. To pass a false belief tasks is to understand a case of misrepresentation.

4. ‘Explicit understanding of representation (mentally modeling the representational relationship = metarepresentation) [...] is necessary for understanding cases of misrepresentation.’

(Perner, 1991, p. 102)

two models

Perner’s representational model

‘representation involves a representational medium that stands in a representing relation to its representational content.’

(Perner, 1991, p. 40)

Davidson’s measurement-theoretic model

We utter sentences to distinguish different beliefs.

This is like using numbers to distinguish temperatues

The numbers play no physical role.

The sentences play no psychological role.

The most sophisticated forms of mindreading involve ...

Hyp 1: ... a representational understanding.

Hyp 2: ... a measurement-theoretic understanding.

predictions?

| Perner’s Representational Model | Davidson’s Measurement-Theoretic Model | |

| Perner’s paradox | ✗ | ✓ |

| FB linked to false sign* | ✓ | (inner saying?!‡‡) |

| FB correlates with alt. naming† | ✓ | ??? |

| incompatible desires before FB‡ | (competition?!††) | ✓ |

*Leekam, Perner, Healey, & Sewell (2008); Perner & Leekam (2008); Sabbagh (2006);

†Doherty & Perner (1998); ‡Rakoczy, Warneken, & Tomasello (2007)

††Priewasser, Roessler, & Perner (2013)

‡‡Geurts (2021)

We lack a shared understanding.

This is a practical problem.

But one we can work around.

step 1 : specify >1 theories of mental states (Perner’s Strategy+)

limit: no knowledge, intention ...!?

Part 1: characterisations of mental states generally

Part 2: characterisations of particular attitudes

dθ-both

action <- facts + objective values

dθ-belief

action <- facts + preferences

‘Diverse Desires’

dθ-desire

action <- subjective probability + objective values

‘Diverse Beliefs’

decision theory

action <- subjective probability + preferences

‘Belief--Emotion’

the postulates of the researcher

the language of the targets of research

neutral on mental

We lack a shared understanding.

This is a practical problem.

But one we can work around.

step 1 : specify a theory of mental states (Perner’s Strategy+)

limit: no knowledge, intention ...!?

step 2 : exploit formal tools

limit ...

limits of decision theory

‘Polly has never ever seen inside this drawer. [...] So, does Polly know what is in the drawer?’

(Wellman & Liu, 2004, p. 539)

also missing:

- strength of justification vs of confidence

- time and the need for planning

- emotion

- mood

- humour

- ethical constraints

- self-regulation

- ...

useful formal model would be too much to hope for

(e.g. Stalnaker, 1999 on knowledge)

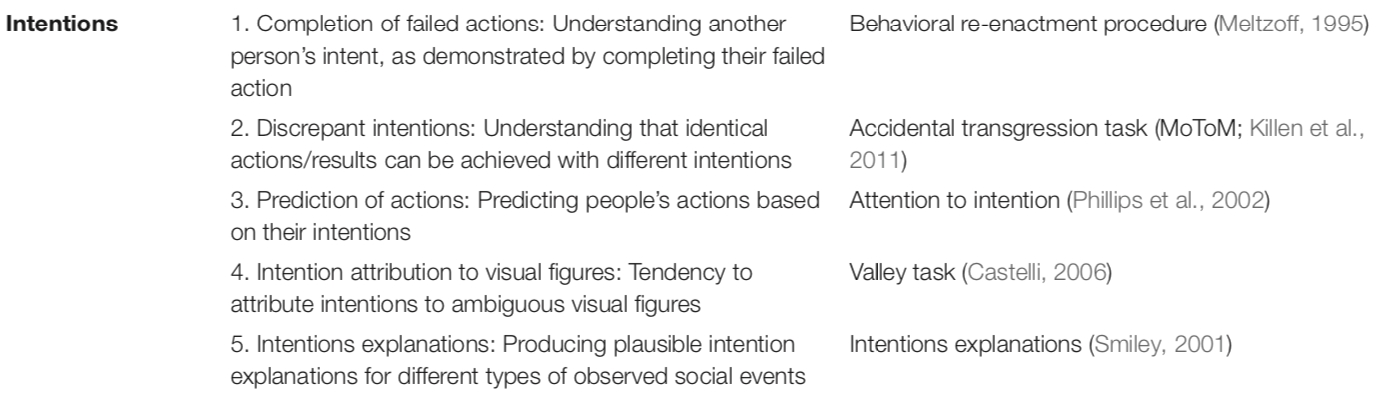

Beaudoin et al. (2020, p. table 2 (part))

~Hunnius ?

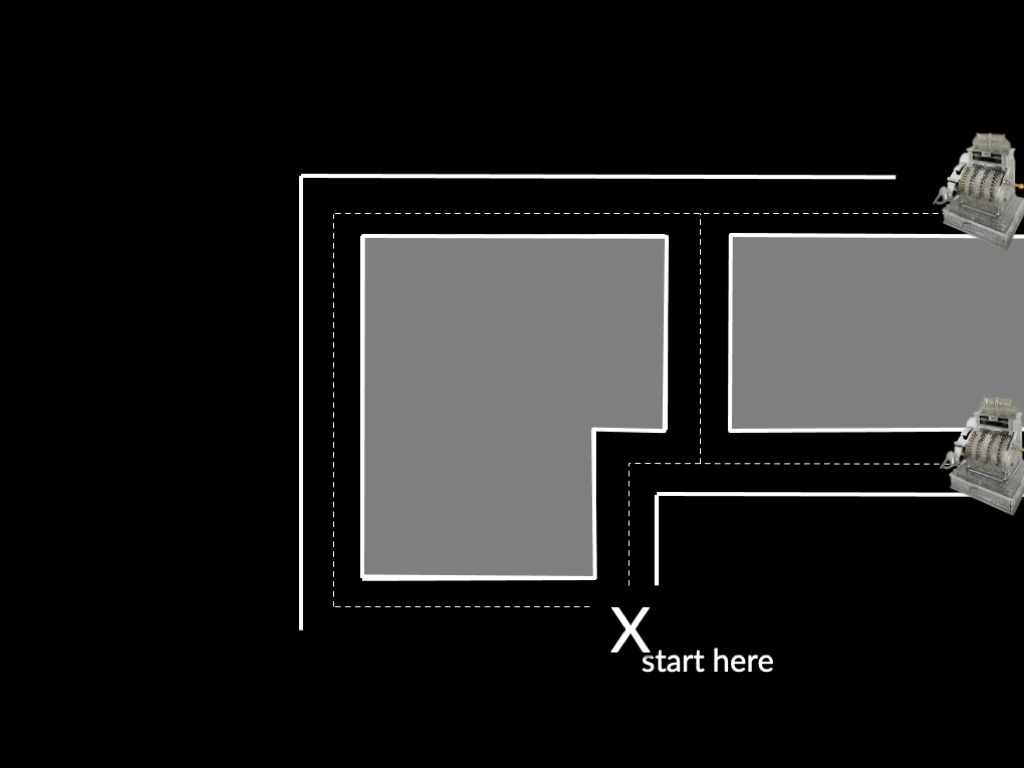

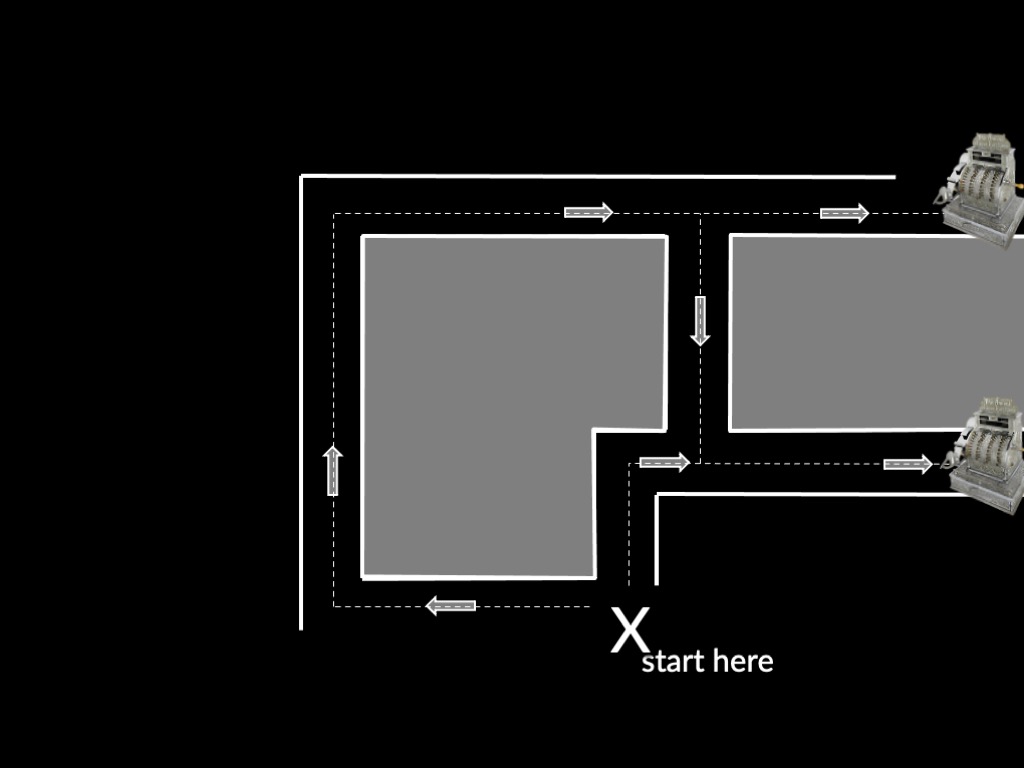

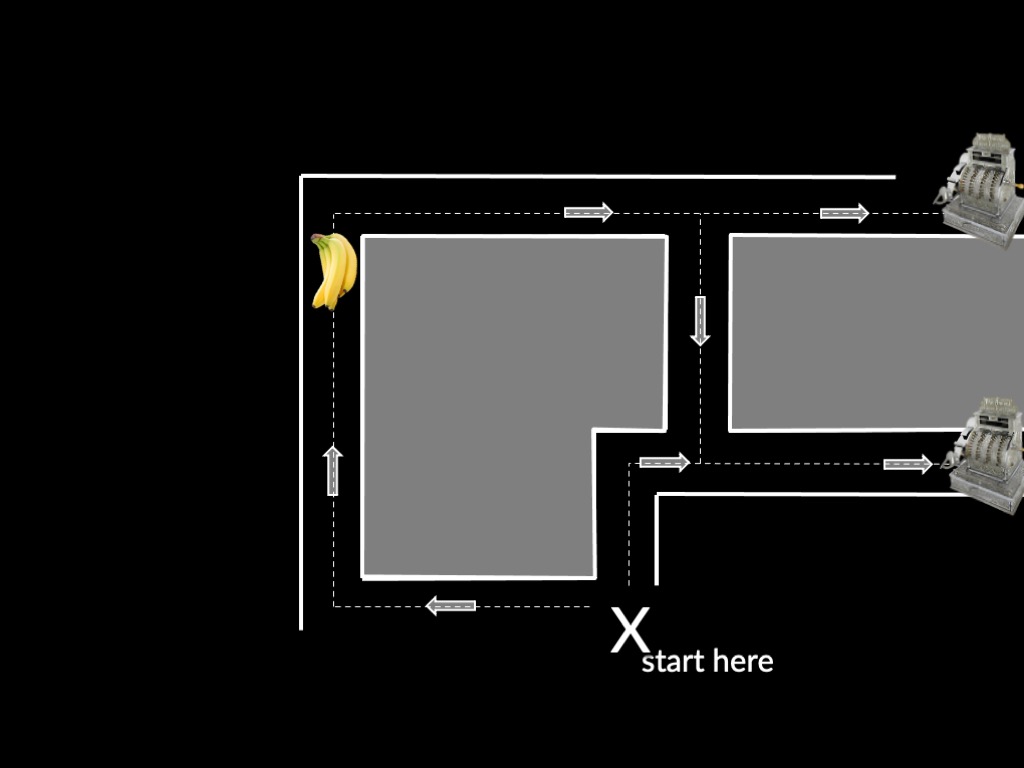

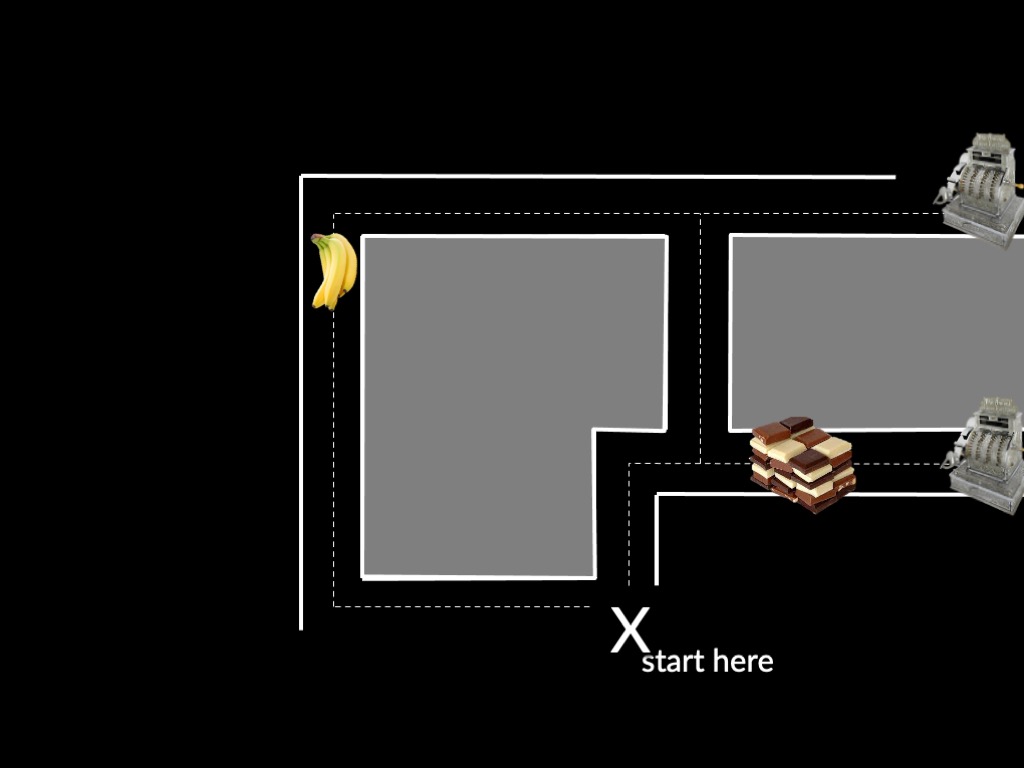

frame 1 : chocolate or bananas?

frame 2 : chocolate only, bananas only, or chocolate+bananas?

Task : predict the route

frame 1 : chocolate or bananas?

frame 2 : chocolate only, bananas only, or chocolate+bananas?

Task : predict the route

the postulates of the

researchers

the language of the

targets

subjective probability + preferences

‘Steve intends to get the chocolate’

coordinating frames specifying different temporal perspectives

‘Steve wants chocolate more than bananas but intends to get both’

We lack a shared understanding.

This is a practical problem.

But one we can work around.

step 1 : specify a theory of mental states (Perner’s Strategy+)

limit: no knowledge, intention ...!?

step 2 : exploit formal tools

limits: time, emotion, mood, ethics ...

step 3 : specify which limits an operationalisation tests

The Myth of

Mind-

reading

Why It Matters & What to Do