Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Dual-Process Theory of Cognitive Development

Metacognitive Feelings and Development

Knowledge of Objects & Minds

online handout

https://handouts.butterfill.com/docs/potsdam_2023/potsdam_2023

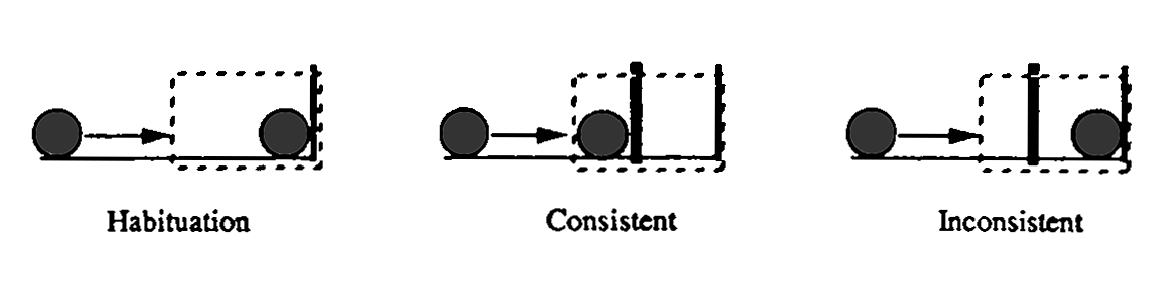

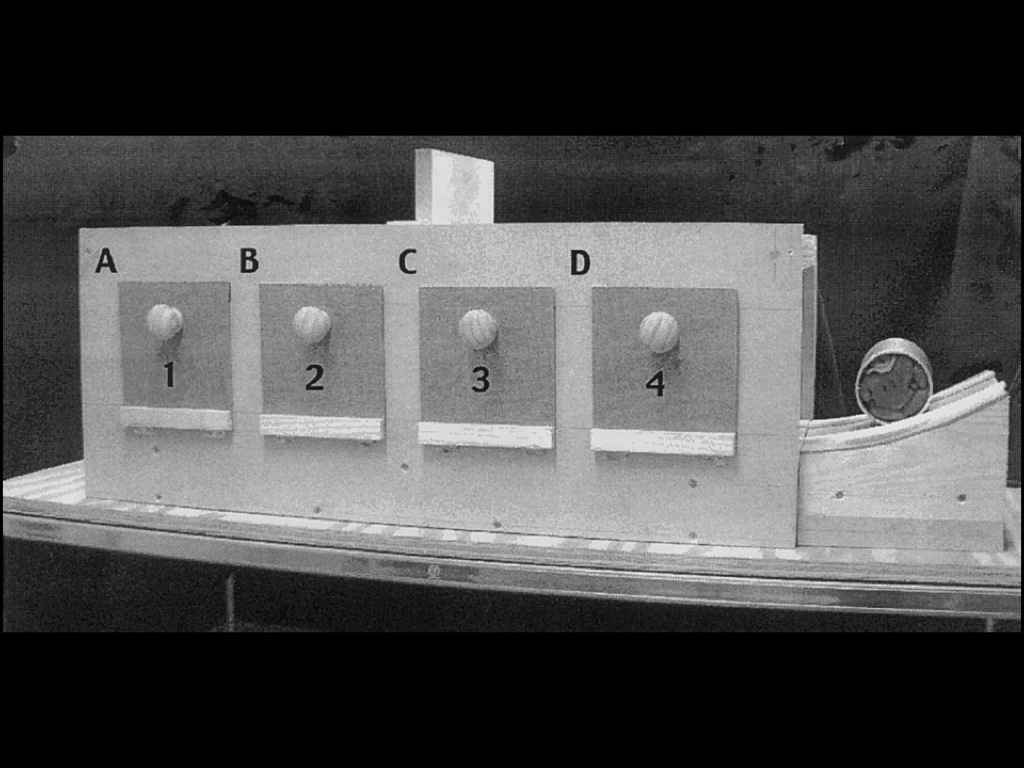

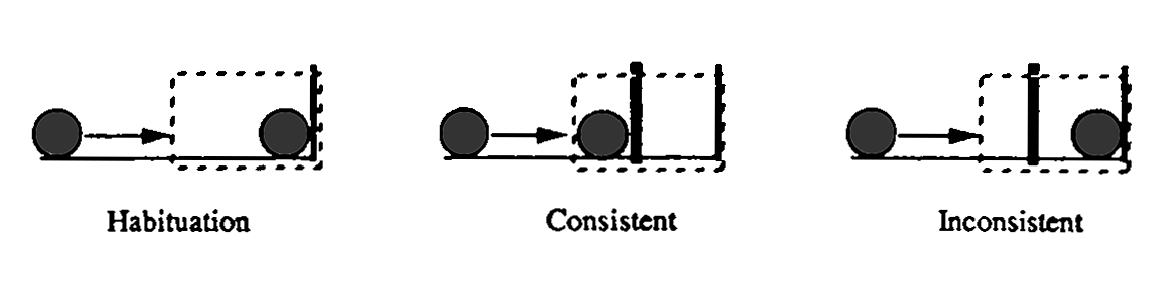

Spelke, Breinlinger, Macomber, & Jacobson (1992, p. figure 6 (part))

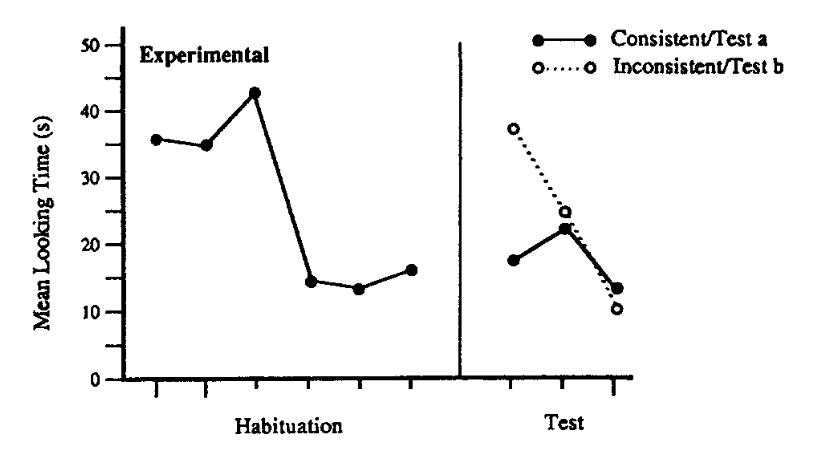

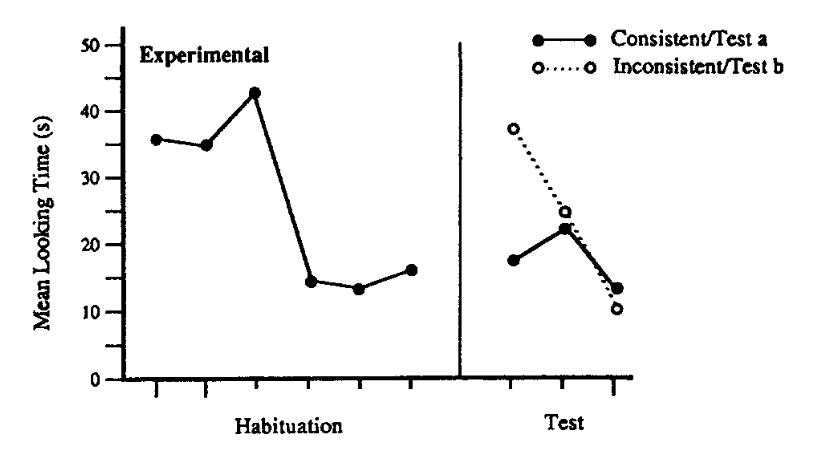

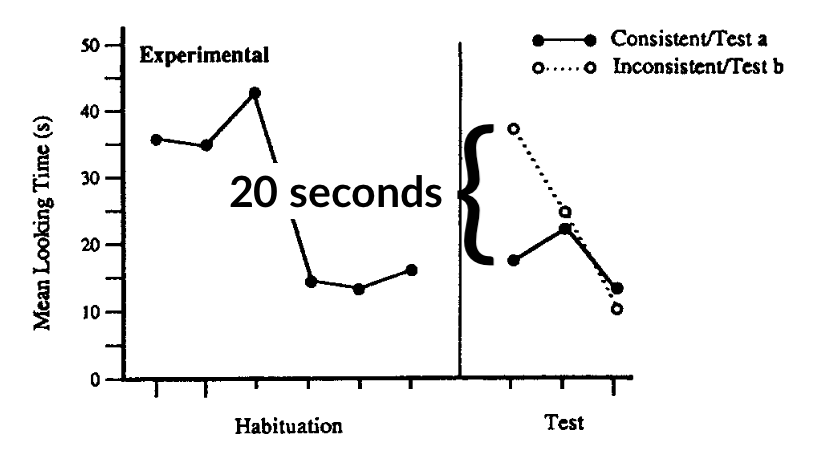

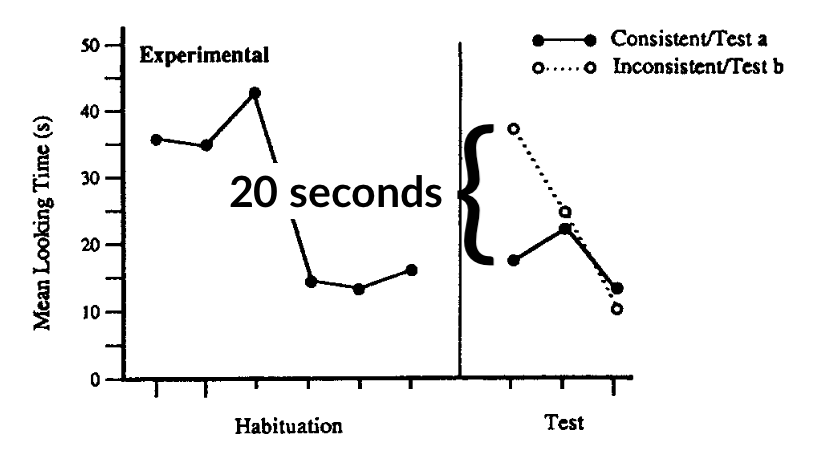

Spelke et al. (1992, p. figure 7 (part))

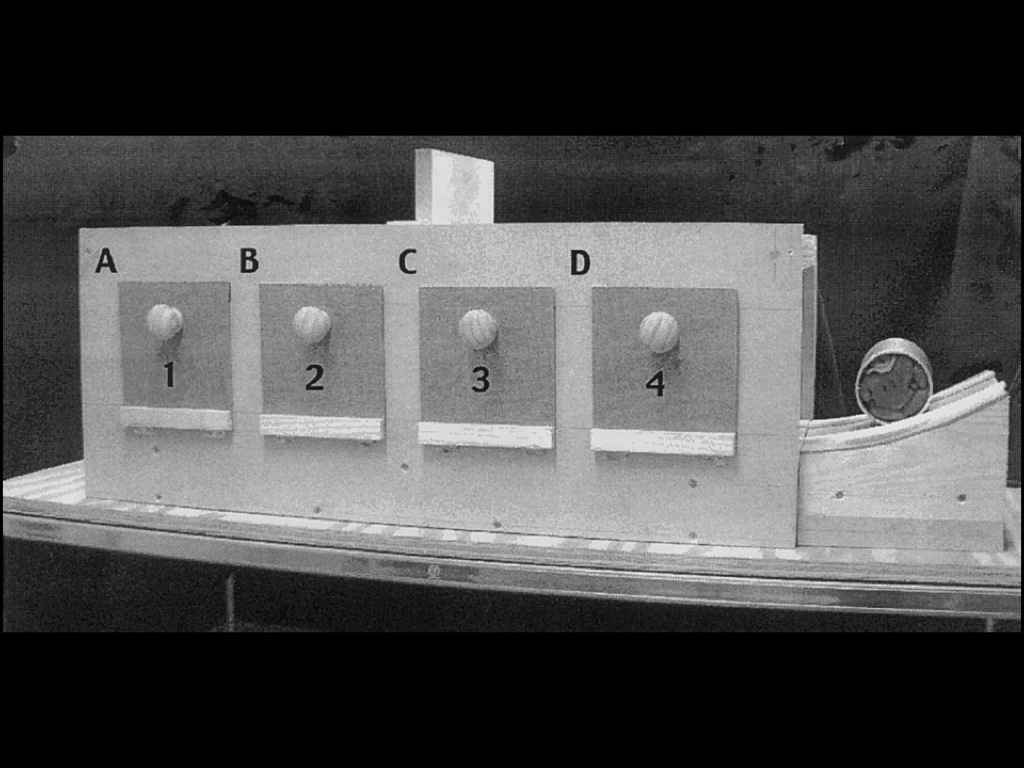

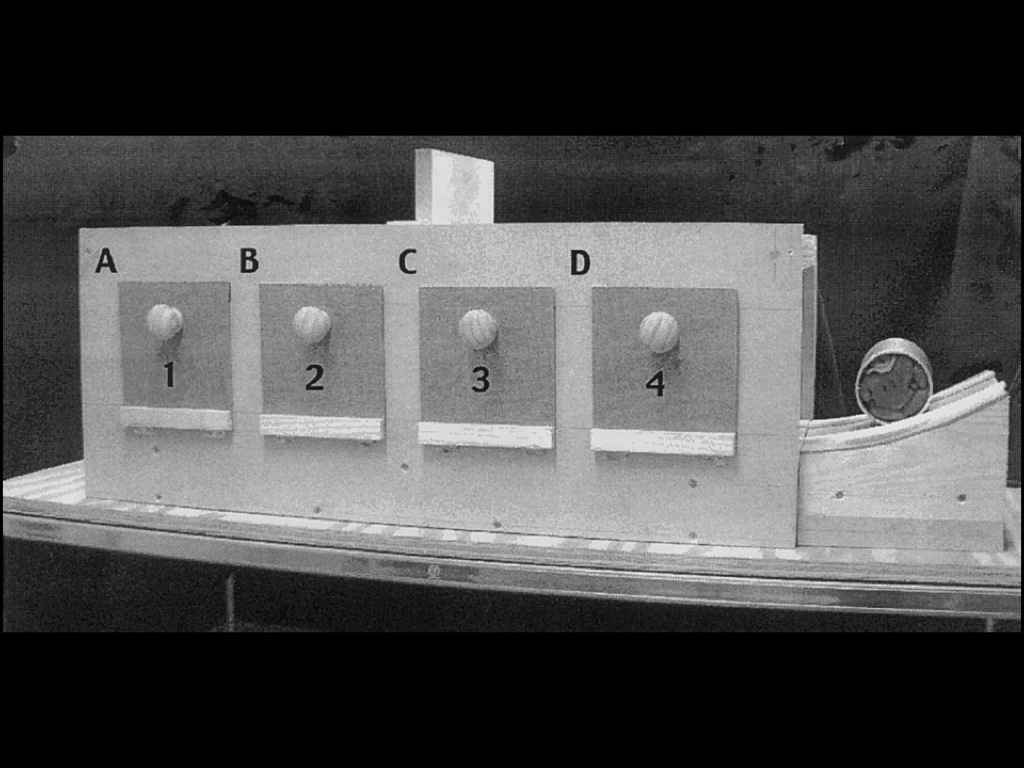

Hood, Cole-Davies, & Dias (2003)

Hood et al. (2003)

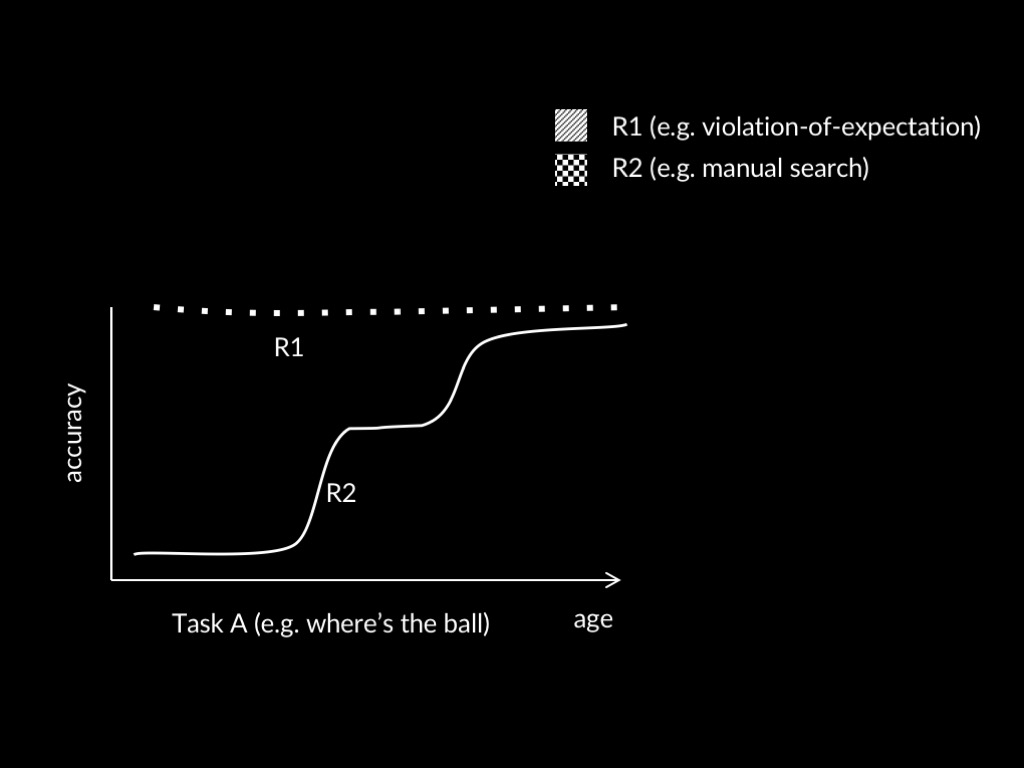

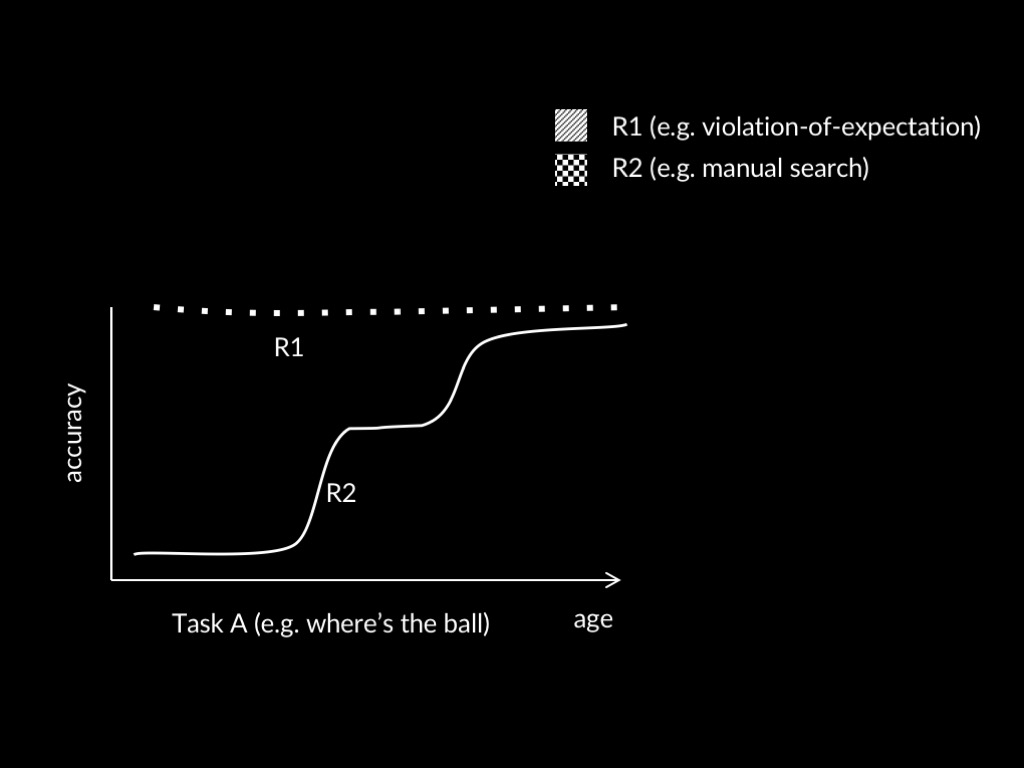

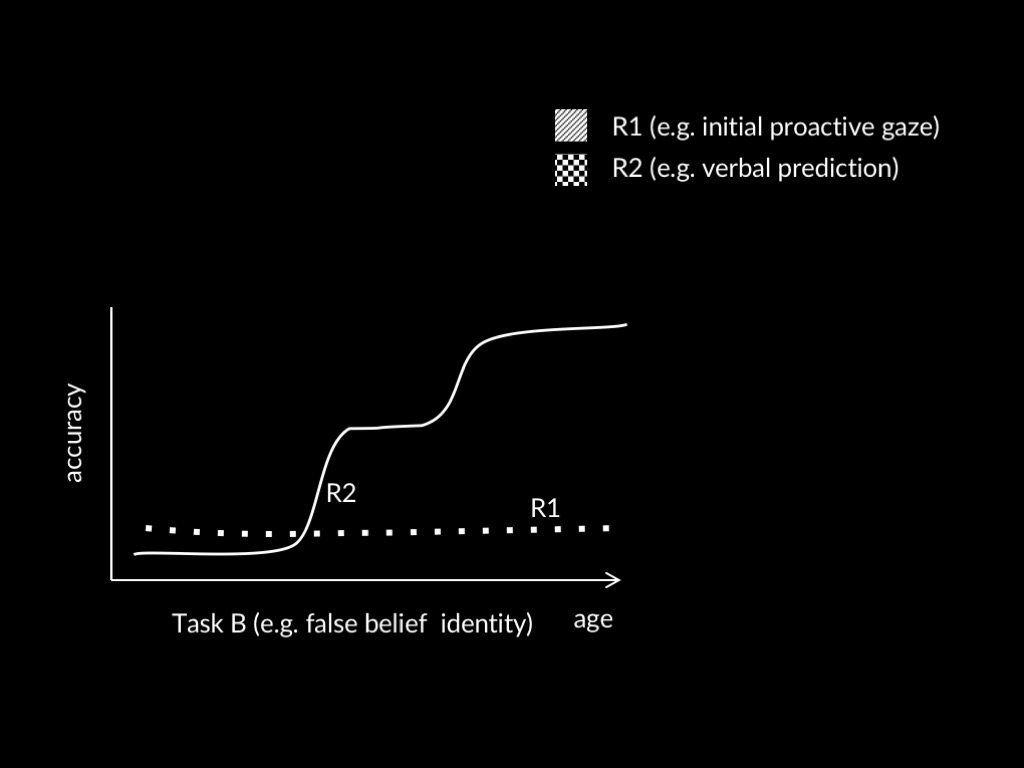

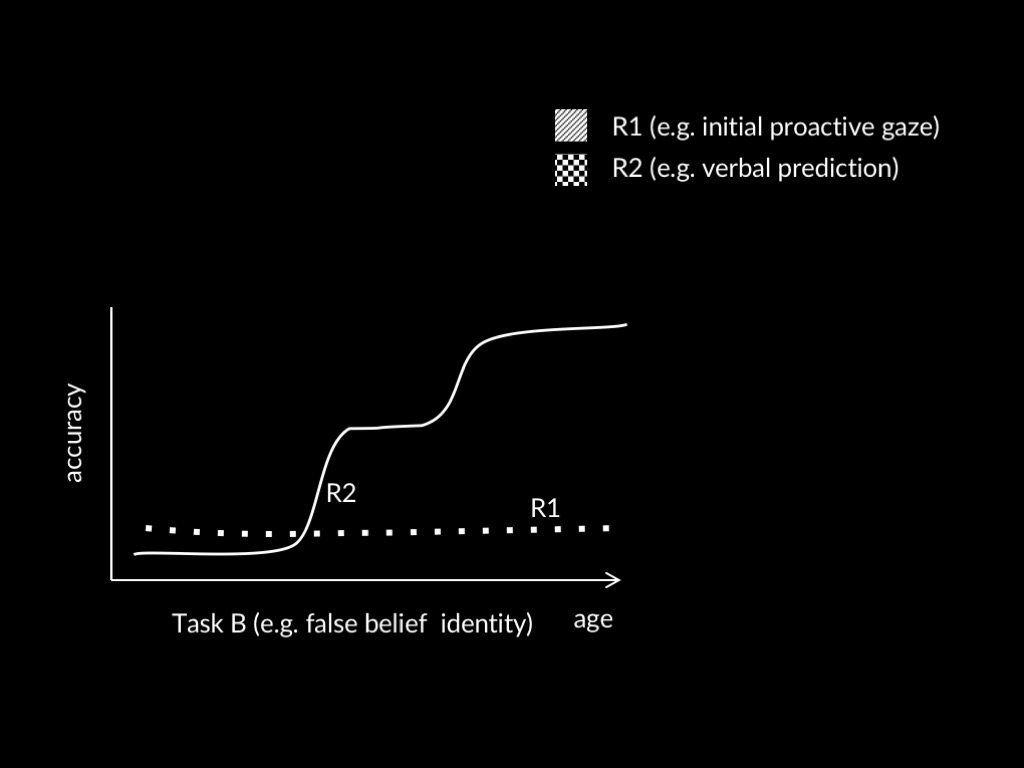

Low et al, 2014 figure 2

Q1

Why do different responses reveal different developmental patterns?

dual-process theory of cognitive development

There are two (or more) processes.

One process is faster than another.

Faster processes are relatively unchanging,

slower processes change across development through learning.

Faster processes dominate anticipatory looking,

slower processes dominate verbal responses.

Q1

Why do different responses reveal different developmental patterns?

?

predictions

Predictions:

[1] Where infants can track objects or beliefs, in adults there will be two distinct processes ...

[2] ... and one adult process will have features in common with the infant process.

Ex: tracking briefly occluded objects

Occurs in 4-month-olds ...

... and we can distinguish two object-tracking processes in adults (e.g. Mitroff et al, 2005).

In adults, one object-tracking process is subject to a signature limit...

... which is also a limit of infants’ object-tracking (e.g. Xu & Carey, 1996)

| domain | mechanism/model | signature limit | source (e.g.) |

| objects | object indexes | featural cues | Xu & Carey, 1996 |

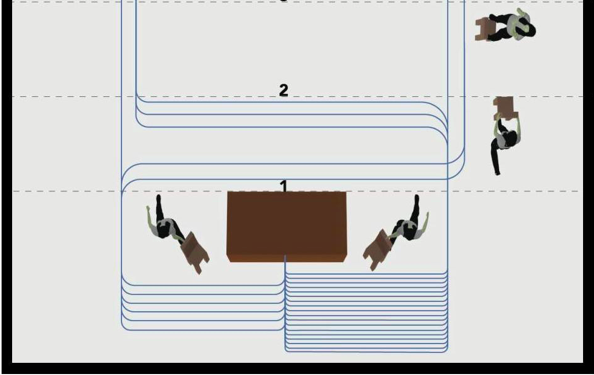

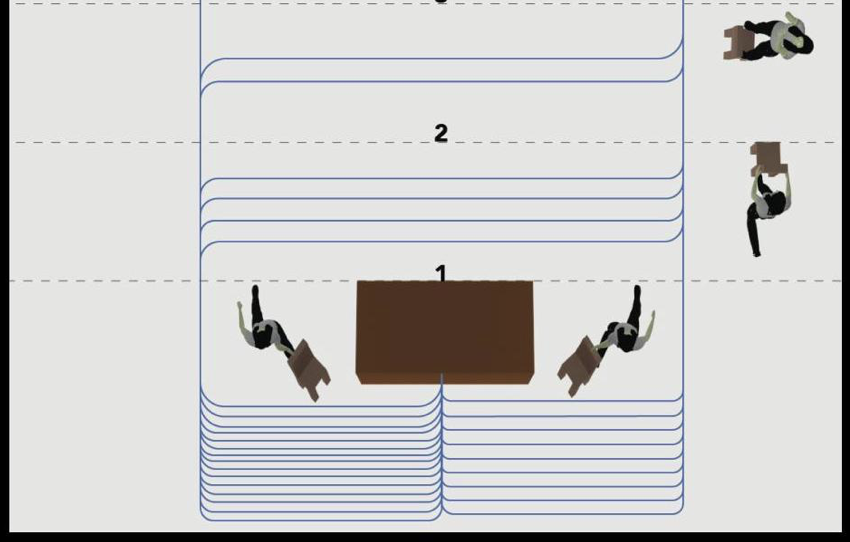

| minds | minimal theory of mind | identity | Edwards & Low, 2017 |

| actions | motor processes | own ability | Kanakogi & Itakura, 2011 |

Q1

Why do different responses reveal different developmental patterns?

Spelke et al. (1992, p. figure 6 (part))

Q2

How could fast processes

influence looking duration?

(And why do they not influence

verbal responses or manual search?)

early-developing,

automatic process

↓

? ? ?

↓

looking duration

(v-of-e or dishabituation)

early-developing,

automatic process

↓

? ? ?

↓

verbal response,

manual search, ...