Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Questions for Discussion

Kagan on

Moral Knowledge

s.butterfill @warwick.ac.uk

‘When I have an intuition it seems to me that something is the case, and so I am defeasibly justified in believing that things are as they appear to me to be. That fact [...] opens the door to the possibility of moral knowledge.’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 167)

‘Edward is the driver of a trolley, whose brakes have just failed. [...] Edward can turn the trolley, killing the one; or he can refrain from turning the trolley, killing the five’ (Thomson, 1976, p. 206).

May Edward turn the trolley?

‘David can take the healthy specimen's parts, killing him, and install them in his [five] patients, saving them. Or he can refrain from taking the healthy specimen's parts, letting his [five] patients die’ (Thomson, 1976, p. 206).

May David kill the healthy person?

‘not even a

prima facie case can be made for the claim that Thomson’s

presentation of the trolley case appeals to intuitions, where these

are construed as judgments with any of features F1--F3.’

(Cappelen, 2012, p. 161)

When thinking about

particular cases we can simply see—immediately, and typically without

further ado—whether, say, a given act would be right or wrong’

(Kagan, 2001, p. 4)

Why may Edward but not David?

How do intuitions enable ethical knowledge?

previously

‘it won't suffice if all we can do is organize these intuitions into systematic patterns.

Instead, [...] we need [...] a moral theory that goes below the surface and [explains] the moral phenomena that are the subject matter of our moral intuitions.’

(Kagan, 2001, p. 10)

now

‘moral intuitions function as inputs into our moral theories in something very much like the way that observations function as inputs into our empirical theories’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 159)

1. ‘If I have the intuition that P, then [...] my belief that P [...] will be justified [until such time (a time which may never come) as] I find reason to reject it.’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 166)

2. ‘what it is to confirm an intuition:

checking it against other intuitions to see if they harmonize in the appropriate ways.’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 172)

Aside: compare Rawls’ on reflective equilibrium

How are ethical intuitions like observations?

‘observation and intuition involve appearances; they are ways that things can seem to me to be the case.

in both cases

[the] fact that things appear to be one way rather than another [...]

provides the tentative justification for [...] believing that things are indeed as they appear to be.’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 164)

The sceptic needs to show there is ‘something especially problematic about moral intuitions, as distinct from others.’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 170)

an obvious thought

‘Convergence Claim, or CC:

If everyone knew all of the relevant non-normative facts, used the same normative concepts, understood and carefully reflected on the relevant arguments, and was not affected by any distorting influence, we and others would have similar normative beliefs.’

(Parfit, 2013, p. 546)

‘Is it [...] true that even if we were perfectly rational and were reflecting on moral questions under ideal conditions we would, nonetheless, continue to have moral disagreements?

[...] Certainly we don’t have any particularly compelling evidence on the question’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 127)

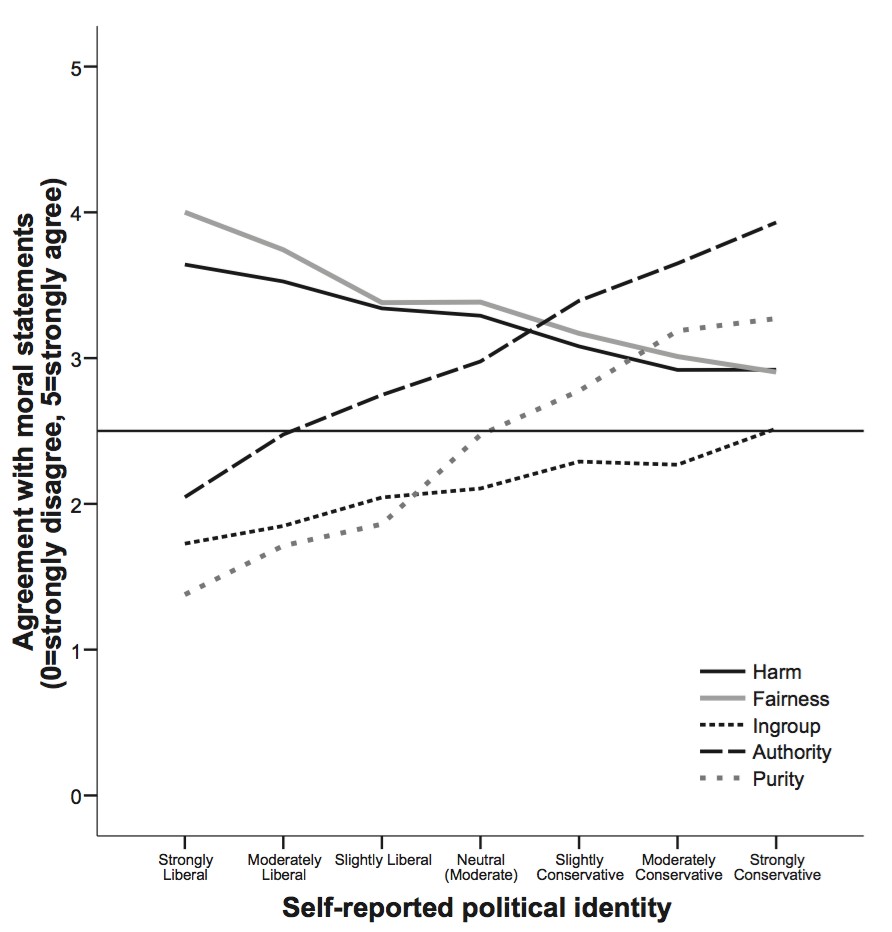

Graham, Haidt, & Nosek (2009, p. figure 3)

cultural variation, illustrated by purity

* gay marriage

* euthanasia

* abortion

* pornography

* stem cell research

* environmental attitudes

(Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto, & Haidt, 2012; Graham et al., 2019)

r1

‘Why shouldn’t we simply take this to be good reason to reject the particular contested intuitions in question? Instead of dismissing all moral intuitions altogether, why not simply disregard (or, conceivably, give less weight to) those intuitions where there is substantial disagreement, and focus instead on intuitions that are indeed widely shared?’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 176)

But aren’t at least some intuitions universal?

‘one finds nearly complete agreement among moral intuitions [...] such as:

It is right to protect one’s children from lethal danger.’

(Bengson et al., 2020, p. 19)

No: maternal infanticide (Hrdy, 1979)

‘a mother in a hunter-gatherer society examines her baby right after birth and [...] makes a conscious decision to either keep the baby or let it die.’ (Hrdy, 2011, p. 198)

r2

‘It doesn’t seem implausible to suggest that some of our

sexual mores (and the intuitions and emotions that support them) may be

the result of our origins as primates rather than, say, bees.

[...]

If anything like this is right, then these are the sorts of intuitions that

we might do well to worry about.’

(Kagan, 2023, pp. 223–4)

r3

‘once we dig below the surface, countless moral disputes do indeed depend, at least in part, on nonmoral issues, and so are really derivative disagreements after all.

[...]

I suspect—though I cannot prove—that the vast majority of our moral disagreements are indeed about derivative moral claims.’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 121)

‘Intuitionism would be challenged if it were true that, even in ideal conditions, there would be many deep disagreements between people who clearly do have moral beliefs, sentiments, or intuitions. [...] they they must defend the claim that, in ideal conditions, there would not be deep and widespread moral disagreements.’

(Parfit, 2013, p. 548)

How are ethical intuitions like observations?

‘observation and intuition involve appearances; they are ways that things can seem to me to be the case.

in both cases

[the] fact that things appear to be one way rather than another [...]

provides the tentative justification for [...] believing that things are indeed as they appear to be.’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 164)

The sceptic needs to show there is ‘something especially problematic about moral intuitions, as distinct from others.’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 170)

another thought

‘In putting forward an account of light, the first point I want to draw to your attention is that it is possible for there to be a difference between the sensation that we have of it, that is, the idea that we form of it in our imagination through the intermediary of our eyes, and what it is in the objects that produces the sensation in us, that is, what it is in the flame or in the Sun that we term ‘light’’

Descartes, The World (AT 3)

physical intuitions

are a source of knowledge

but only within limits

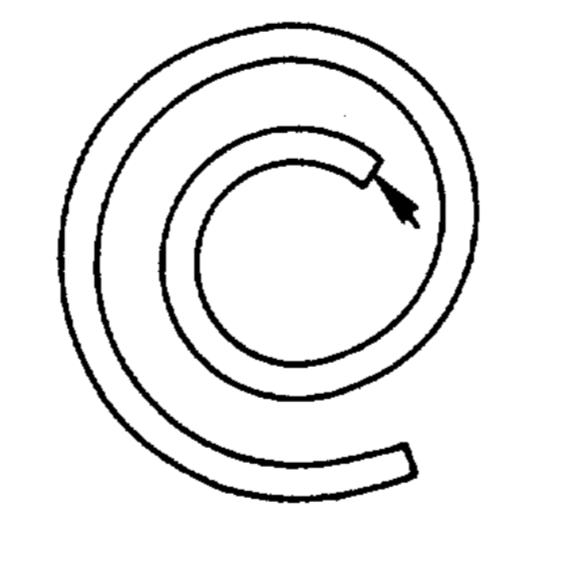

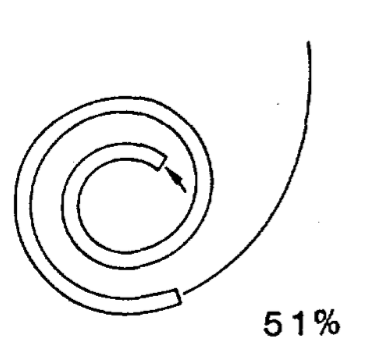

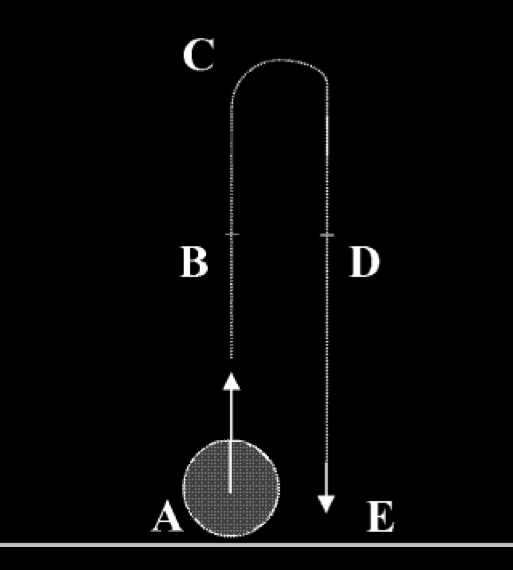

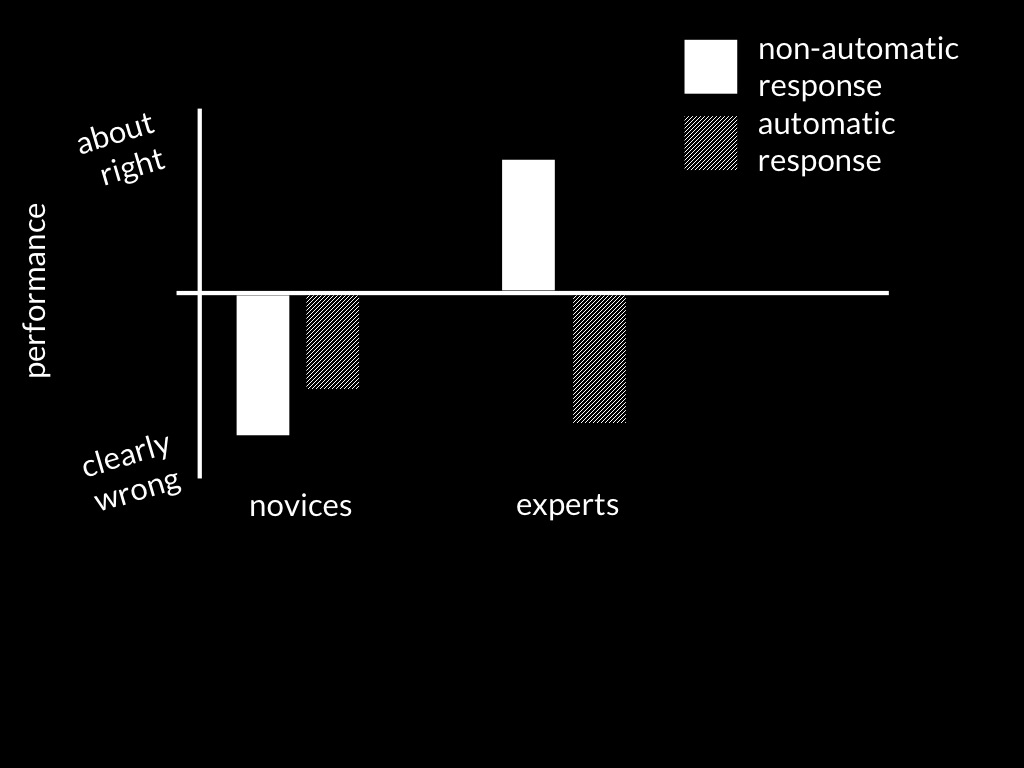

McCloskey, Caramazza, & Green (1980, p. figure 2B)

McCloskey et al. (1980, p. figure 2D)

Kozhevnikov & Hegarty (2001, figure 1)

simplified from Kozhevnikov & Hegarty (2001)

simplified from Kozhevnikov & Hegarty (2001)

reliable

unreliable

physical intuitions

straight tubes

horizontal motion

curved tubes

vertical motion

reliable

unreliable

physical intuitions

straight tubes

horizontal motion

curved tubes

vertical motion

ethical intuitions

food sharing in small bands

cooperative breeding

trolley problems

climate change

‘ultimately we would like to identify the mechanisms which can lead to mistaken intuitions, since that might sometimes help us to confirm which intuitions are erroneous.’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 175)

‘there must be some evolutionary advantage in having a faculty that [...] gets at least some basic moral truths right.’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 184)

cooperative breeding (Hrdy, 2011)

food sharing (Kaplan & Gurven, 2005)

small-scale cooperation

managing shamans and other leaders (Boehm et al., 1993)

‘When I have an intuition it seems to me that something is the case, and so I am defeasibly justified in believing that things are as they appear to me to be. That fact [...] opens the door to the possibility of moral knowledge.’

(Kagan, 2023, p. 167)

But only within limits.

What does Kagan claim about the role of intuition in gaining moral knowledge? Is it so?

What is the relation between Kagan’s position and Rawls’ notion of reflective equilibrium?

Is Kagan right about the parallel between physical and moral intuitions?

Given Kagan’s position, what are the limits of moral knowledge?

appendix

Are case-specific intuitions a source of ethical knowledge?

for

successful cognitive practice

(Bengson et al., 2020)

analogy with observation in physics

(Kagan, 2023)

anti

extraneous effects on intuition

(Rini, 2013; Sinnott-Armstrong, 2008)

cultural varation

(McGrath, 2008)

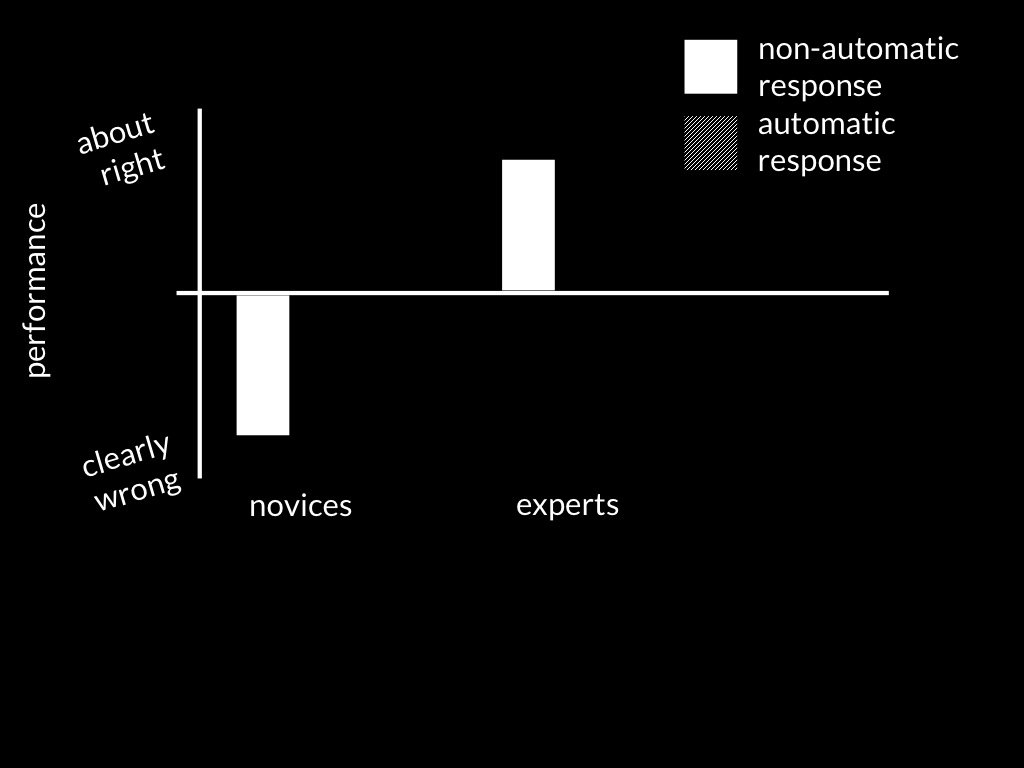

speed—accuracy trade-offs

(Greene, 2014)

bad control

(Cecchini, 2024)