object indexes + metacognitive feelings

↓

? ? ?

↓

knowledge of objects

\section{Development Is Rediscovery}

This guess gives rise to a further question (which I want to articulate

but won’t attempt to answer).

In asking how the operations of object indexes might give rise to

patterns in looking duration, we have been concerned with what happens a

short interval of time.

But the guess about metacognitive feelings raises a question

about the course of development in the first months or years of life.

Let me explain.

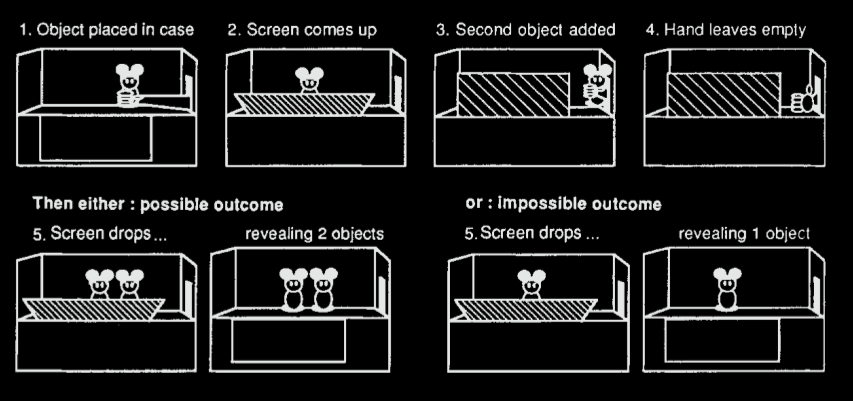

In the beginning Spelke and others conjectured that infants’

abilities to track briefly occluded objects were a consequence of their

having core knowledge for objects.

This conjecture is related to the later hypothesis about object indexes.

The idea is that we can further specify the mechanisms that realise

infants’ core knowledge of physical objects by identifying it with

two things: a system of object indexes and a system capable of representing

physical objects motorically.

So core knowledge of objects is not one thing but three:

it is realised by (i) a system of object indexes; (ii) associated

metacognitive feelings and (iii) a capacity

to represent affordances motorically.

There was always a question about how infants’ core knowledge about

objects might explain the emergence of knowledge knowledge

(that is, knowledge proper) about objects.

Now this question becomes, What is the role of a system of object

indexes in the emergence in development of knowledge of physical

objects?

In short, How do you get from object indexes to knowledge?

Answers to these questions typically rely on

\emph{The Assumption of Representational Connections}: the transition involves

operations on the contents of core knowledge states, which transform them into

(components of) the contents of knowledge states.

This Assumption is required by almost any current account

of the developmental emergence of knowledge.

It is required, for example, by

Spelke’s suggestion that mature understanding of objects, number,

and mind derives from core knowledge by virtue of core knowledge

representations being assembled (Spelke, 2000);

claims by Leslie and others

that modules provide conceptual identifications of their inputs

(Leslie, 1988);

Karmiloff-Smith’s representational re-description

(Karmiloff-Smith, 1992);

and Mandler’s claim

that ‘the earliest conceptual functioning consists of a redescription

of perceptual structure’ (Mandler, 1992).

But the Assumption of Representational Connections requires, of course, that core

knowledge provides a conceptual identification of objects and some of their

properties such as location or size, or at least that it involves standing in some

kind of intentional relation to these things.

[Key point is that since metacognitive feelings don’t have [relevant] content,

direct representational connections between core knowledge and knowledge

proper are impossible.]

But recall the guess about metacognitive feelings linking object

indexes to patterns of looking duration.

If this guess is right, then it is not true that

core knowledge provides a conceptual identification of objects.

And it is not true that having core knowledge involves standing in any

kind of intentional relation to objects and their properties.

This means that we must reject

Assumption of Representational Connections.

And rejecting this Assumption makes the question about development particularly

difficult to answer.

It means that rather than assembing or redescribing representations,

development must be a process of rediscovery.

The step from metacognitive feelings to knowledge is like the step

from feeling electric shocks to understanding electricity.

So coming to know simple facts about particular physical

objects may begin with object indexes and the

metacognitive feelings these give rise to, but it does not end there.

Interpreting the metacognitive feelings may involve interacting with

objects, learning to use tools, and perhaps interacting with others

and objects simultaneously.

Coming to know facts about physical objects is a matter of

rediscovering things already implicit in a system of object indexes.

Some might object that development can’t require such rediscovery

because it would be hopelessly inefficient to require things already

encoded to be learnt anew.

But rediscovery is an elegant solution to a practical problem.

If you are building a survival system you want quick and dirty

heuristics that are good enough to keep it alive: you don’t

necessarily care about the truth.

If, by contrast, you are building a thinker, you want her to be

able to think things that are true irrespective of their survival value.

This cuts two ways.

On the one hand, you want the thinker’s thoughts not to be

constrained by heuristics that ensure her survival.

On the other hand, in allowing the thinker freedom to pursue the

truth there is an excellent chance she will end up profoundly

mistaken %(Malebranche?)

or deeply confused %(Hegel?)

about the nature of physical objects.

So you don’t want thought contaminated by survival heuristics and you

don’t want survival heuristics contaminated by thought. Or, even if

some contamination is inevitable, you want to limit it.

%So you want inferential isolation.

This combination is beautifully achieved by giving your thinker a

system or some systems for tracking objects and their interactions

which appear early in development, and also a mind which allows her

to acquire knowledge of physical objects gradually over months or

years, taking advantage of interactions with objects as well as

social interactions about objects—providing, of course, that the

two are not directly connected but rather linked only very loosely,

via metacognitive feelings.

Of course, if

the Assumption of Representational Connectedness is wrong and

development is rediscovery,

then core knowledge can only play a relatively modest role in explaining

the developmental acquisition of knowledge.

Instead, simple froms of social interaction, perhaps including

referential communication or even communication by language

will play a key role in the developmental emergence of knowledge of

simple facts about physical objects.

And of course they can only do this if abilities for social interactions

including communication do not already presuppose such knowledge.

But this is a topic for further inquiry.

For now, I mainly want to sugggest that we must either reject my claim

that core knowledge influences its subject only through modifications

of the body, of behaviour and attention and of phenomenology

or else face up to the challenge of explaining how development

could be a process, not of recycling representations already

available in the very first months of life, but of rediscovery.