What is

core knowledge?

How do infants track briefly occluded objects?

An early idea was that infants’ earliest abilities involved

knowledge of physical objects. On this view, infants know simple principles

governing how objects behave (for example, that they follow continuous paths through

space and time) and infants know the locations of some briefly occluded objects.

In an early paper Spelke offered a strong statement of this view.

‘objects are conceived: Humans come to know about an object’s ... boundaries ... in ways like those by which we come to know about its material composition or its market value’

Spelke 1988, p. 198

But there are now some compelling objections to the view that

infants know the facts about the locations of briefly occluded objects ...

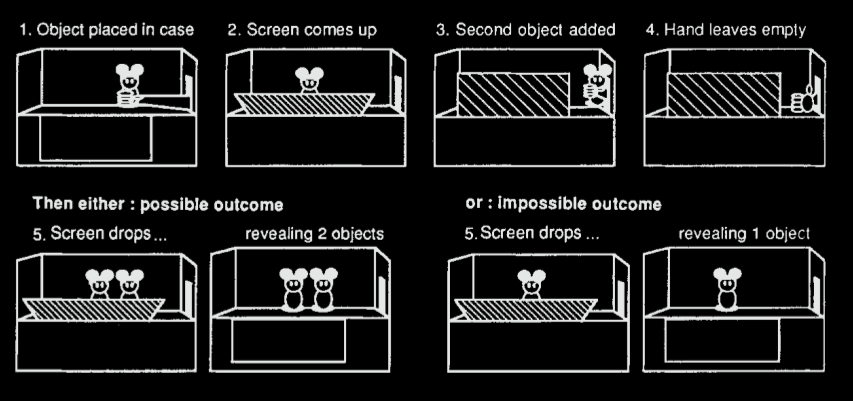

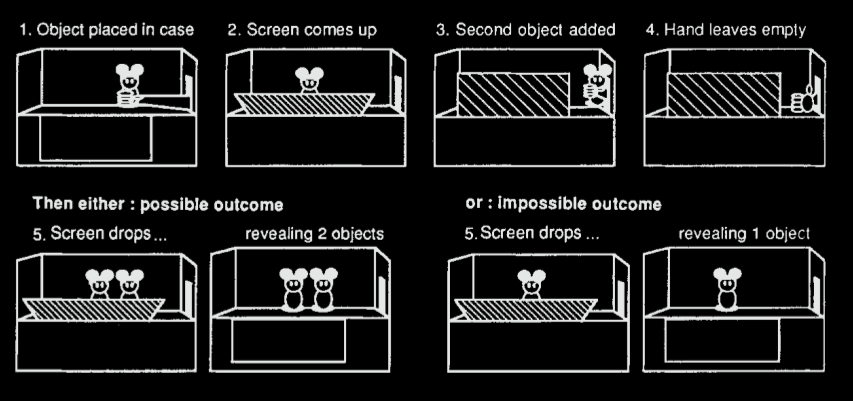

To illustrate, consider an ingenious experiment by Shinskey & Munakata (2001).

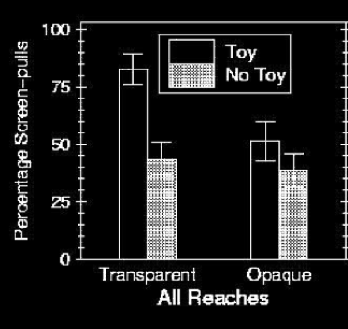

There was an opaque screen that could rotate between lying flat on the ground and being raised to conceal a toy behind it.

Shinskey and Munakata also used a second piece of apparatus just like the first except that the screen was transparent rather than opaque.

They reasoned that infants would quite often pull the screen forwards just for fun, regardless of what is behind it.

However, they also guessed that when infants know there is an interesting toy behind the screen, then they will pull it forwards more often than when they know that there is nothing behind the screen.

This is just what happened when infants were presented with the apparatus involving a transparent screen:

they sometimes pulled the screen forwards when there was no toy behind it, but they pulled it forwards significantly more often when the toy was behind it.

What happened when infants were presented with the opaque screen?

Here infants pulled the screen forwards no more often when they had observed a toy being placed behind it then when they had observed that there was nothing behind it.

This is evidence that seven-month-old infants do not know that a toy they have very recently seen hidden behind a screen is behind the screen.

After all, since knowledge guides action we would expect infants who know that a toy is behind an opaque screen to pull the screen forward more often than infants who know there is nothing behind the screen, just as they do when the screen is transparent.

More than two decades of research strongly supports the view that

infants fail to search for objects hidden behind barriers or screens

until around eight months of age (Meltzoff & Moore, 1998, p. \ 202) or

maybe even later (Moore & Meltzoff, 2008).

Researchers have carefully controlled for the possibility that infants’

failures to search are due to extraneous demands on memory or the

control of action.

We must therefore conclude, I think, that four- and five-month-old

infants do not have beliefs about the locations of briefly occluded

objects.

It is the absence of belief that explains their failures to search.

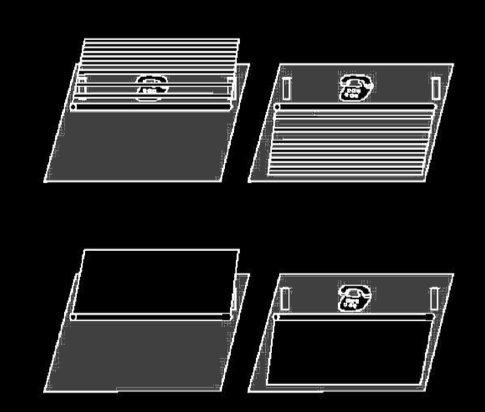

Here are their results with 7-month old infants.

We are interested in whether infants were more likely to pull the screen forwards when the

object was present than when it was absent.

Since infants wanted the toy, if they knew it was behind the barrier they should have pulled

forward the barrier more often when the toy was behind it.

This is exactly what they did when the barrier was transparent.

But look what happens when the barrier is opaque, so that the toy is not visible to infants

when they have to prepare the pulling action: they no longer pull the barrier more often

when the toy was behind it.

This is good evidence that 7 month olds do not know facts about the locations of objects

they cannot perceive.

And this is not isolated evidence; for example, Moore & Meltzoff (2008) use a different

methods also involving manual search to provide converging evidence for this conclusion.

But now we have a problem ...

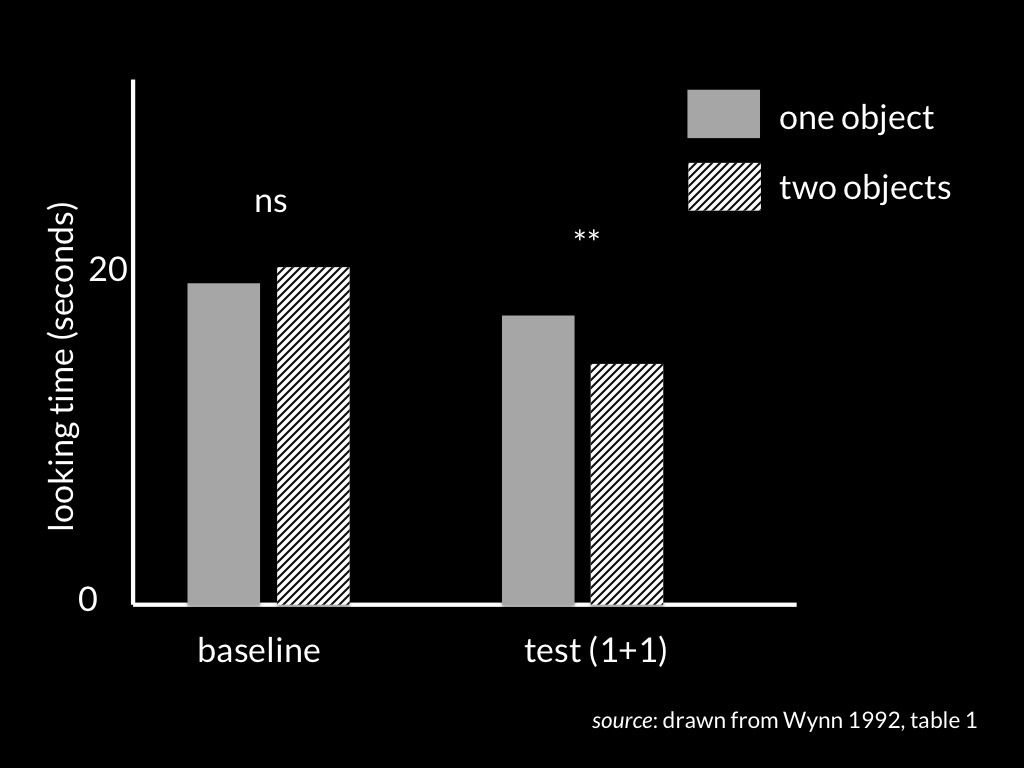

Because this point is controversial, I want to mention one further

piece of the puzzle.

What happens if we change the way an object disappears.

Instead of occluding it?

There’s much evidence that

infants will reach for an object hidden in darkness (Jonsson & Von Hofsten, 2003, p. e.g.).

But what happens if instead of measuring reaching we measure looking times?

Charles & Rivera (2009) compared what happens when an object is momentarily hidden behind a screen with what happens when an object is momentarily hidden by darkness.

They used a trick with light and mirrors so that for some of the infants, the object did not reappear when the screen came up or the light returned.

Surprisingly, five-month-old infants’ looking times indicated that an expectation had been violated only when the object was hidden behind a screen but not when hidden by darkness.

So five-month-olds not only sometimes fail to search for hidden objects but

also sometimes fail to look longer when a momentarily hidden object fails

to reappear as if by magic.

I think this pattern of findings is good evidence against the hypothesis

that four- or five-month-olds have beliefs about, or knowledege of,

the locations of

unperceived objects.

After all,

a belief is essentially the kind of state that can inform actions of any

kind, whether they involve looking, searching with the hands or anything

else.

While this view still has adovates (notably Renee Baillargeon), many researchers have

rejected this view because it generates too many incorrect predictions.