Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Norms-like Patterns

step 1

change the question

Greene et al’s question:

‘We developed this theory in response to a long-standing philosophical puzzle known as the trolley problem’

(Greene, 2015, p. 203; see Greene, 2023)

Which factors influence responses to dilemmas?

- whether an agent is part of the danger or a bystander;

- whether an action involves forceful contact with a victim;

- whether an action targets an object or the victim;

- how the victim is described (Waldmann et al., 2012).

- whether there are irrelevant alternatives (Wiegmann, Horvath, & Meyer, 2020);

- order of presentation (Schwitzgebel & Cushman, 2015);

‘almost all these confounding factors influence judgments, along with a number of others’

(Waldmann et al., 2012, pp. 288–90).

‘almost all these confounding factors influence judgments, along with a number of others [...] The research suggests that various moral and nonmoral factors interact in the generation of moral judgments about dilemmas’

(Waldmann et al., 2012, pp. 288–90).

step 2

distinguish ethical abilities

Greene et al’s assumption:

‘morality is a suite of cognitive mechanisms that enable otherwise selfish individuals to reap the benefits of cooperation.’

(Greene, 2015, p. 198)

ethical abilities

- care

- cooperation (Boyd & Richerson, 2022)

- inequality aversion (Brosnan & Waal, 2014)

- balance authority vs autonomy (Wengrow & Graeber, 2018)

- discern impurity (Chakroff, Russell, Piazza, & Young, 2017)

- ...

step 3

no principles

If not principles, then what?

‘When it comes to morality, the most basic issue concerns our capacity for normative guidance: our ability to be motivated by norms of behavior ...’

(FitzPatrick, 2021)

normative attitudes?

‘norms are characterized by general acceptance of particular normative principles within the group in question.’

(Brennan, Eriksson, Goodin, & Southwood, 2013, p. 94)

‘How does a habit [mere pattern] differ from a rule? ... A social rule has an ‘internal’ aspect ...

there should be a critical reflective attitude to certain patterns of behaviour as a common standard ...

this should display itself in criticism (including self-criticism), demands for conformity, and in acknowledgements ..., all of which find their characteristic expression in the normative terminology of ‘ought’’

(Hart, 1994, pp. 55–7)

1. Where there are discourse referents there are norms (of correctness).

2. Infants don’t have normative attitudes about referential communication (nor adults?).

∴

3. There is normative guidance without normative attitudes.

It feels wrong but isn’t.

->

a form of normative guidance without normative attitudes?

norm-like pattern

a pattern which exists because

(i) there are behaviours which uphold the pattern;

(ii) some or all of these behaviours have the collective goal of upholding the pattern; and

(iii) the catalysts are the subjects.

goal != intention

distributive vs collective

‘The injections prolonged her life.’

‘The goal of their actions is to prolong her life.’

collective goal — each of their actions is directed to this goal, and that is true in the collective (not distributive sense)

How could some agents’ actions have a collective goal?

If

there is a single outcome, G, such that

(a) our actions are coordinated; and

(b) coordination of this type would normally increase the probability that G occurs.

then

there is an outcome to which our actions are directed where this is not, or not only, a matter of each action being directed to that outcome,

i.e.

our actions have a collective goal.

between habits and rules

norm-like pattern

a pattern which exists because

(i) there are behaviours which uphold the pattern; and

(ii) some or all of these behaviours have the collective goal of upholding the pattern; and

(iii) the catalysts are the subjects.

How could upholding a pattern

be a collective goal of our actions

other than through

natural selection,

explicit intentions

or normative attitudes?

normatively-catalytic behaviours ...

1. ... can be subtle, even unintentional ...

- moving closer/away

- smiling/frowning

- fluently/disfluently interacting

- ostensive complicance/covert violation

- selecting/deselecting

- ...

2. ... are sometimes caused by feelings ...

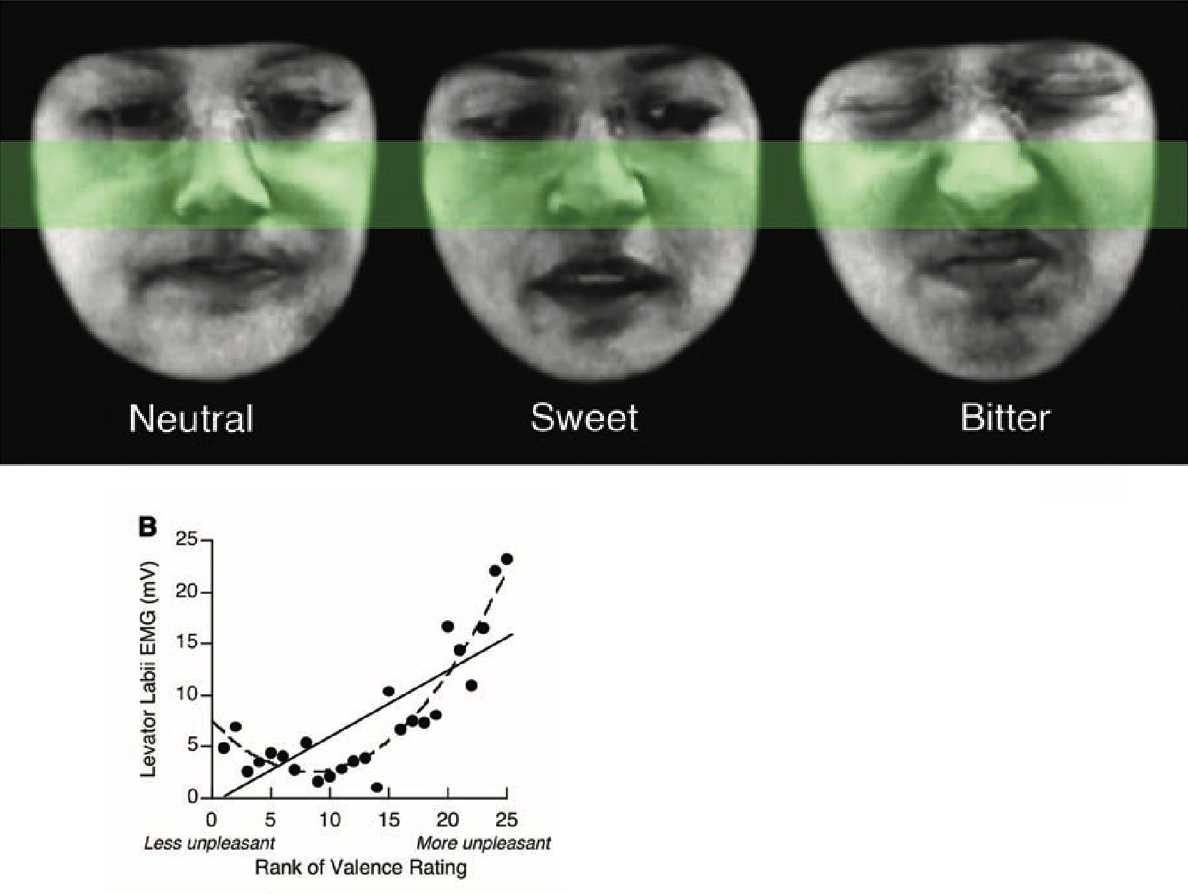

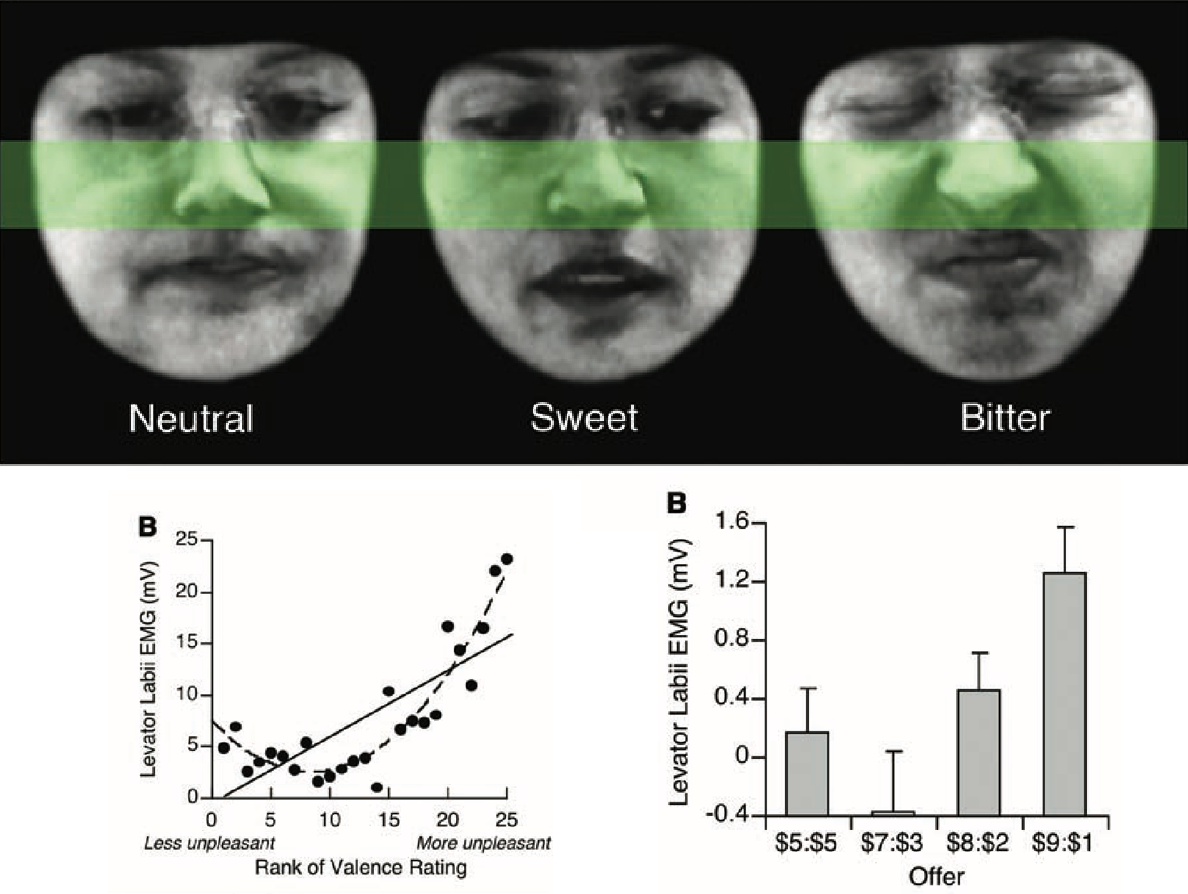

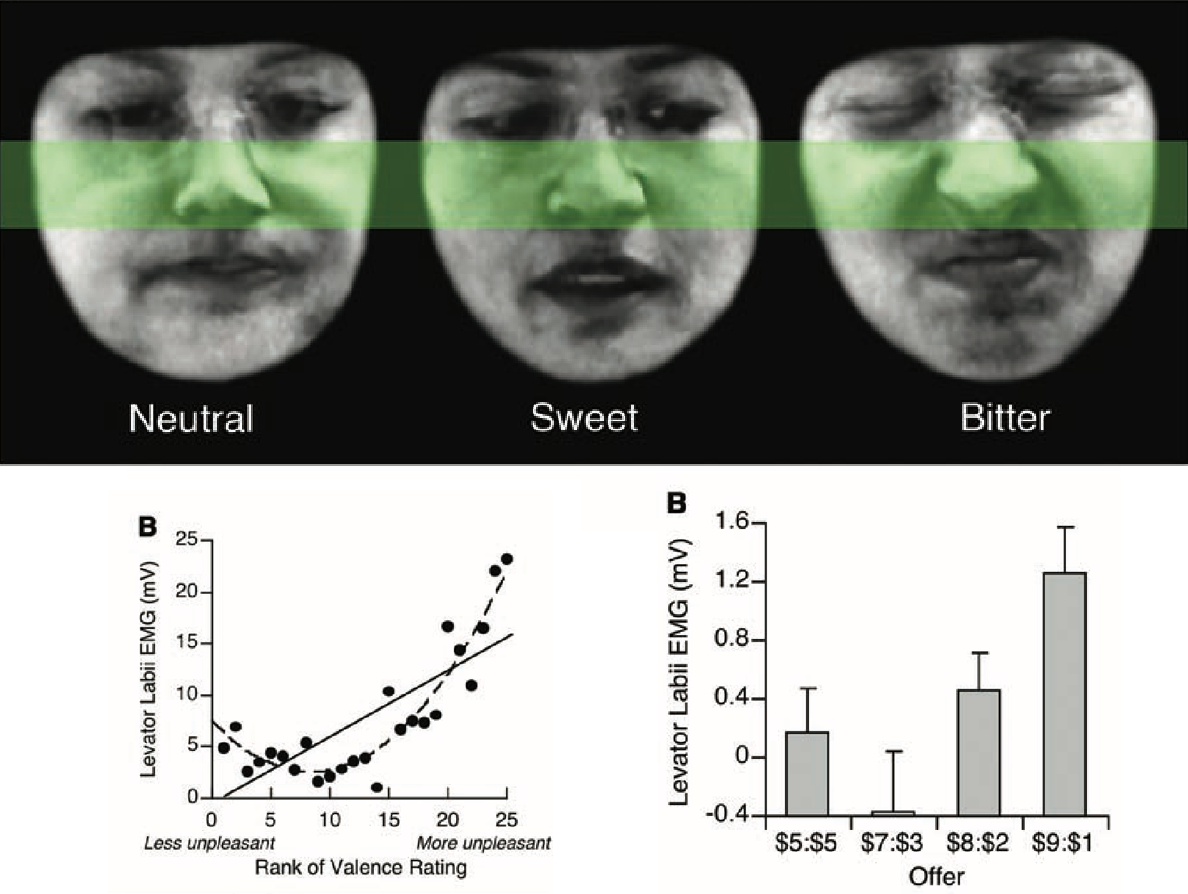

Chapman et al. (2009, p. fig 1,3 (part))

Chapman et al. (2009, p. fig 1,3 (part))

Violations cause feelings; feelings influence behaviours.

bitterness

(Chapman et al., 2009; Eskine et al., 2011).

disgust

(Tracy, Steckler, & Heltzel, 2019; Vanaman & Chapman, 2020; Chapman & Anderson, 2013; Lai, Haidt, & Nosek, 2014; Giner-Sorolla & Chapman, 2017)

happiness

(Gawronski, Conway, Armstrong, Friesdorf, & Hütter, 2018)

limits: effects of feelings are

- complex

(Tracy et al., 2019)

- small in size

(Landy & Goodwin, 2015; Chapman, 2018; Piazza, Landy, Chakroff, Young, & Wasserman, 2018; Giner-Sorolla, Kupfer, & Sabo, 2018)

- culturally mediated

(Terrizzi, Shook, & Ventis, 2010)

normatively-catalytic behaviours ...

1. ... can be subtle, even unintentional ...

- moving closer/away

- smiling/frowning

- fluently/disfluently interacting

- ostensive complicance/covert violation

- selecting/deselecting

- ...

2. ... caused by feelings ...

3. ... which are modulated by joint action ...

4. ... because the feelings enable us to create norm-like patterns.

conjecture: minimal normative guidance

Disgust, bitterness, happiness, social pain, and other feelings

function to enable us to create patterns of behaviour,

which are thereby norm-like.

It feels wrong but isn’t.

How could violating a norm-like pattern feel wrong?

It doesn’t, as such.

At most it creates a metacognitive feeling of disfluency.

But as I am a catalyst as well as a subject,

I may anticipate feelings of disgust, bitterness or pain

or I may anticipate behaviours that function as sanctions;

and these may bias me to interpret a feeling of disfluency as indicating wrongness.