Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Notes and Slides

online handout

Motor Mindreading?

[email protected] & [email protected]

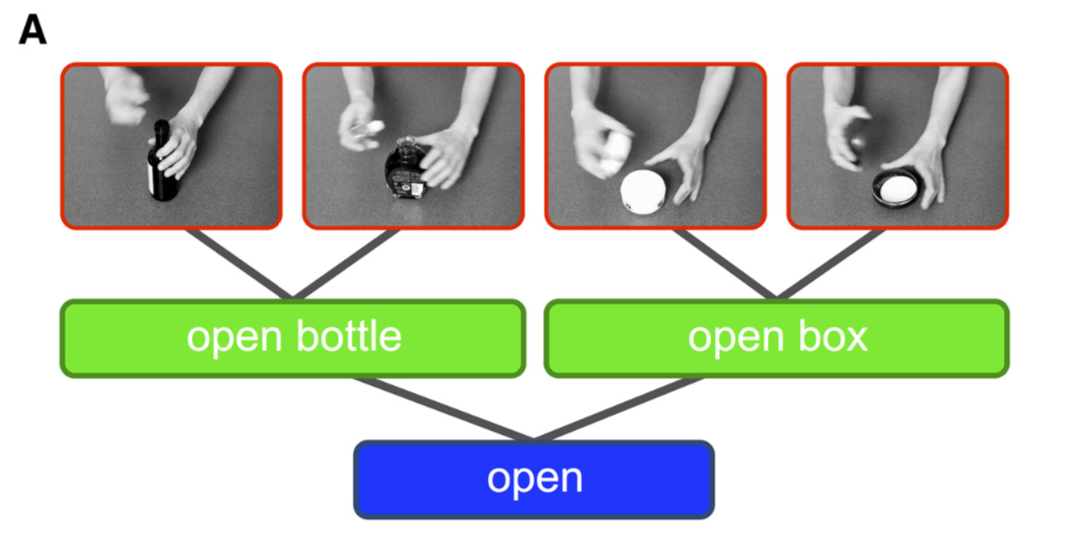

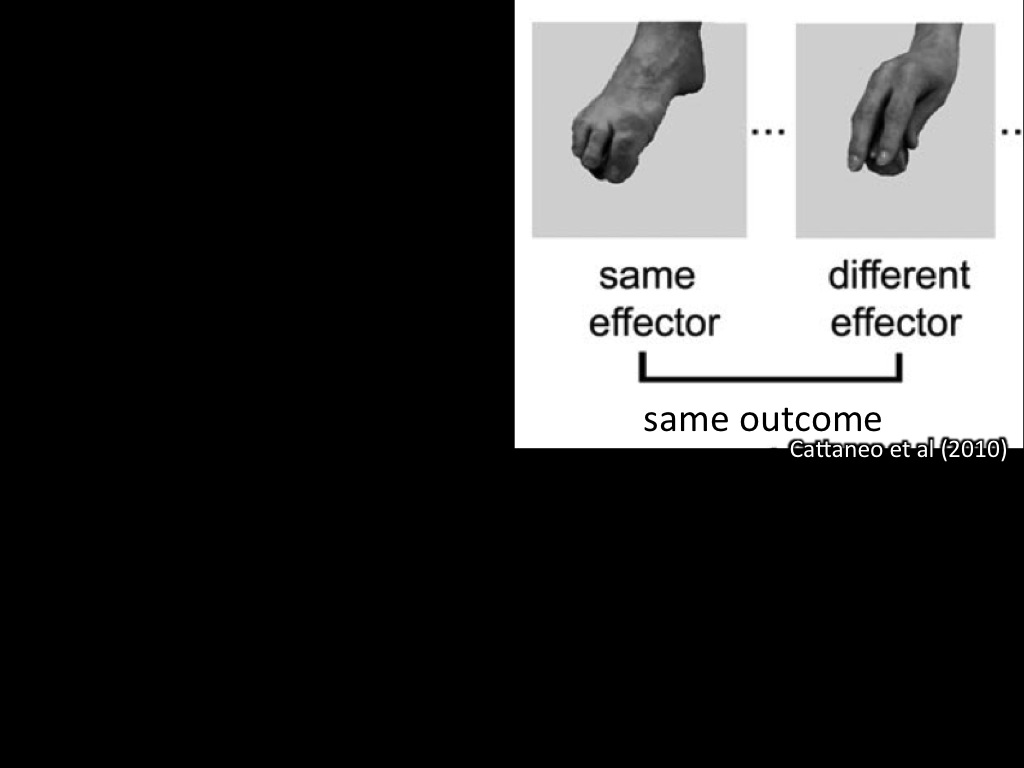

‘“mirror” areas [...] encode concrete representations of observed actions

(e.g.,the action involved in opening a particular bottle)

rather than abstract, higher level representations

(e.g., the goal “to open”; Wurm & Caramazza, span 2019; Wurm & Lingnau, 2015).’

(Heyes & Catmur, 2022, p. 155)

Wurm & Lingnau (2015, p. figure 1, part)

but ...

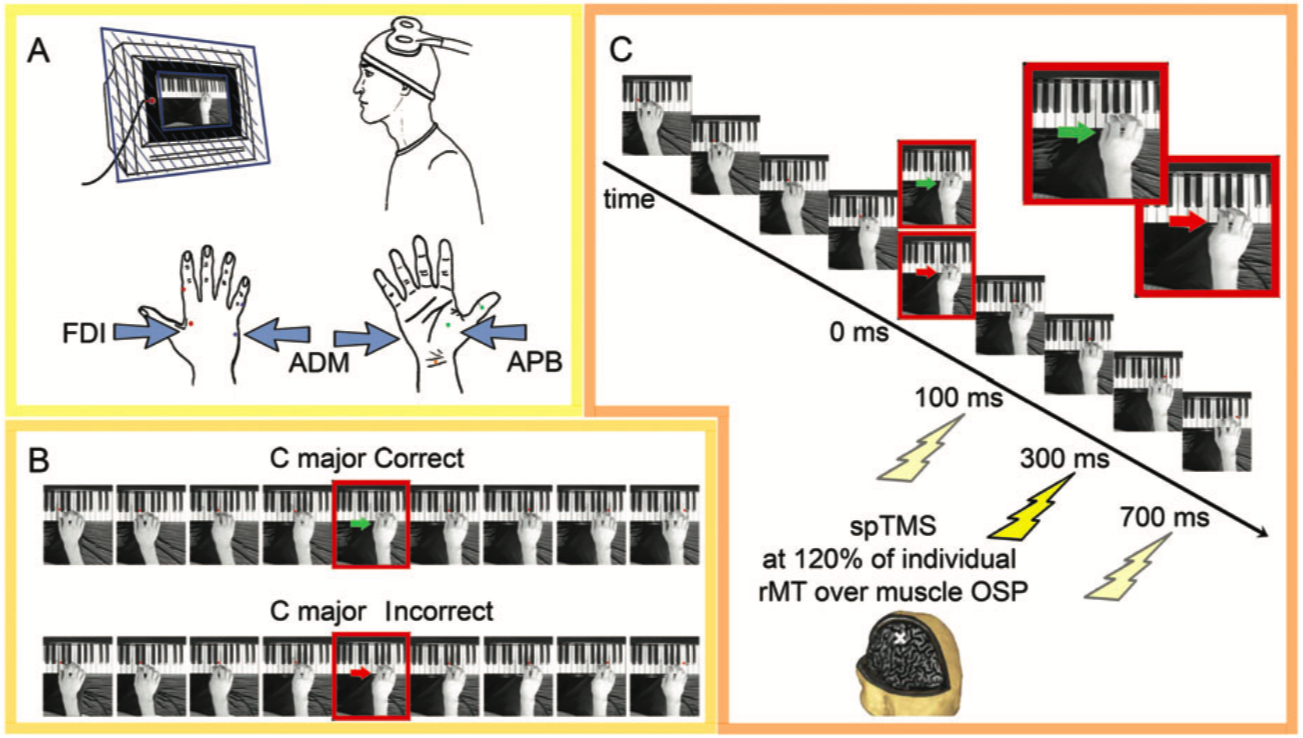

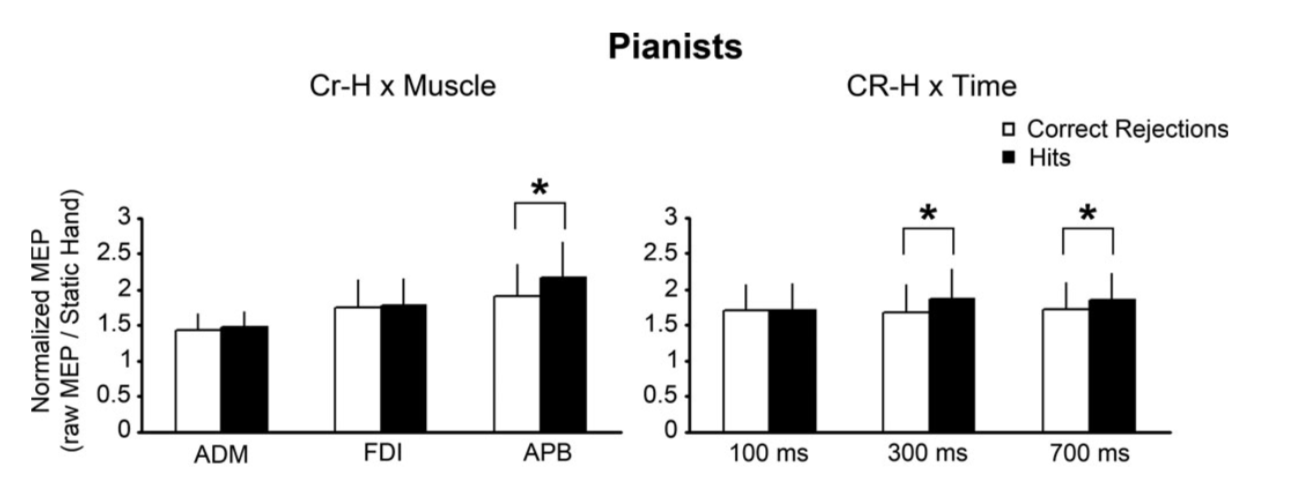

mirror activation contingent on correctness of the action

Candidi, Maria Sacheli, Mega, & Aglioti (2014, p. figure 1)

Some markers of motor representation ...

1. are unaffected by variations in kinematic features but not goals

2. are affected by variations in goals but not kinematic features

concrete vs abstract ?

lexically concrete

Motor representations in action observation carry information about opening this bottle not that one (Wurm & Lingnau, 2015).

kinematically abstract

Motor representations carry information about goals such as opening (Rizzolatti & Sinigaglia, 2016),

and about correctness (Naish et al., 2014).

-- concrete actions, not lexical action categories

-- distal goals, not kinemtic features

?

concrete vs abstract ?

lexically concrete

Motor representations in action observation carry information about opening this bottle not that one (Wurm & Lingnau, 2015).

kinematically abstract

Motor representations carry information about goals such as opening (Rizzolatti & Sinigaglia, 2016),

and about correctness (Naish et al., 2014).

-- concrete actions, not lexical action categories

-- distal goals, not kinemtic features

?

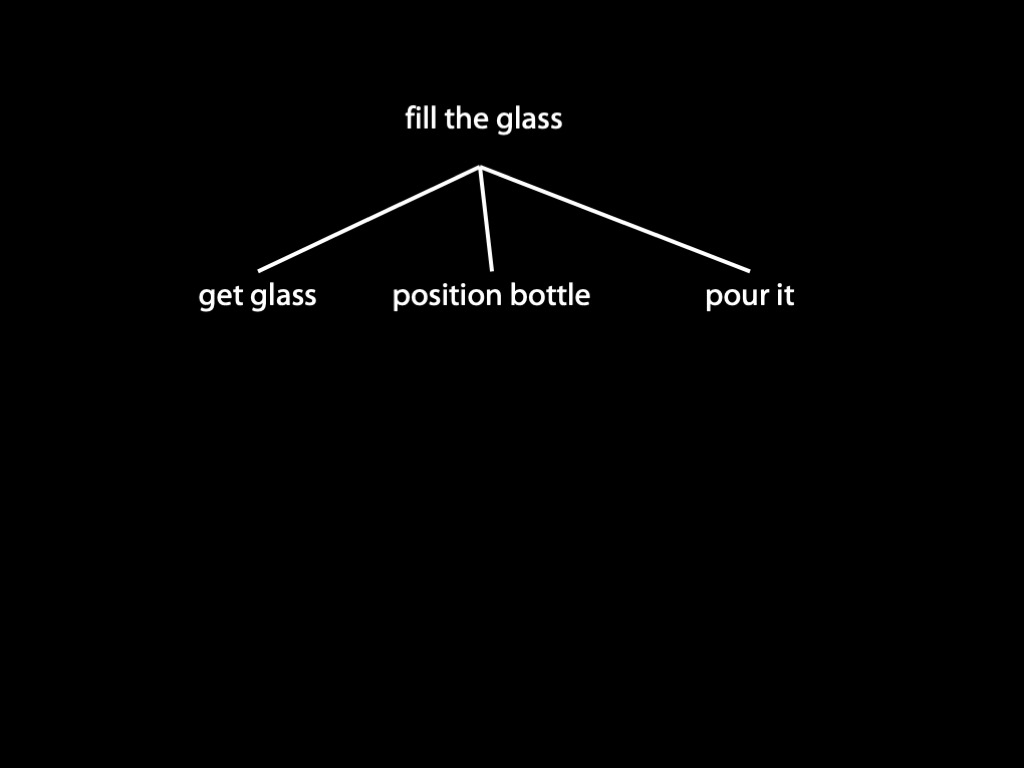

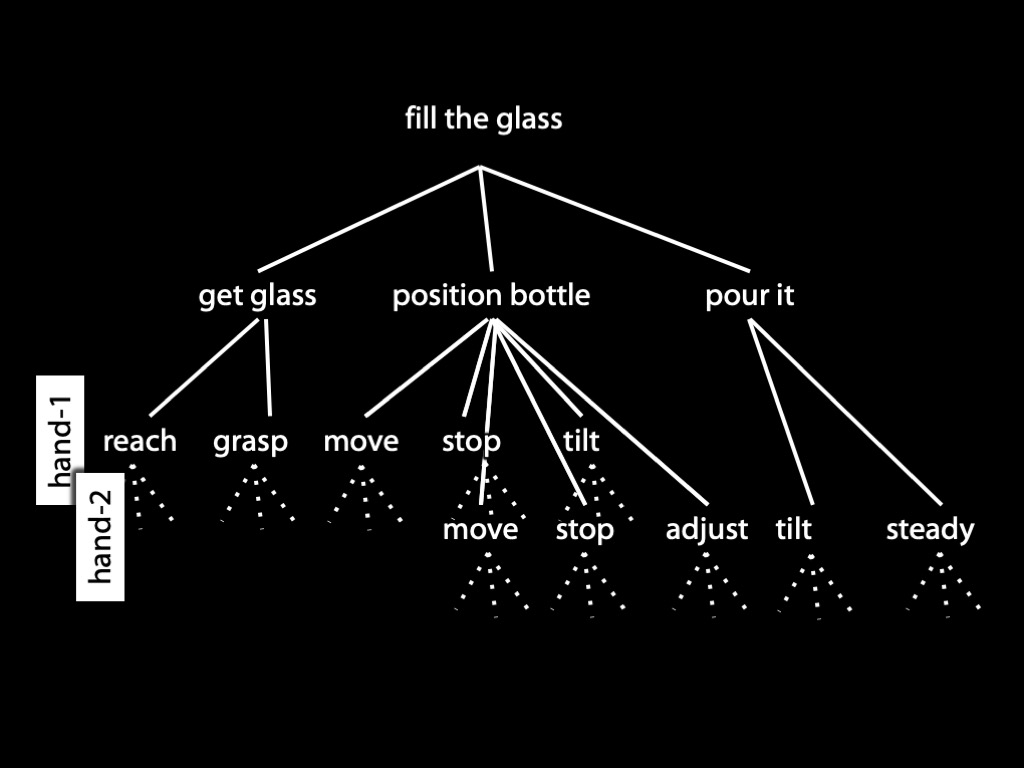

1. motor goal tracking

2. motor mindreading

The Background

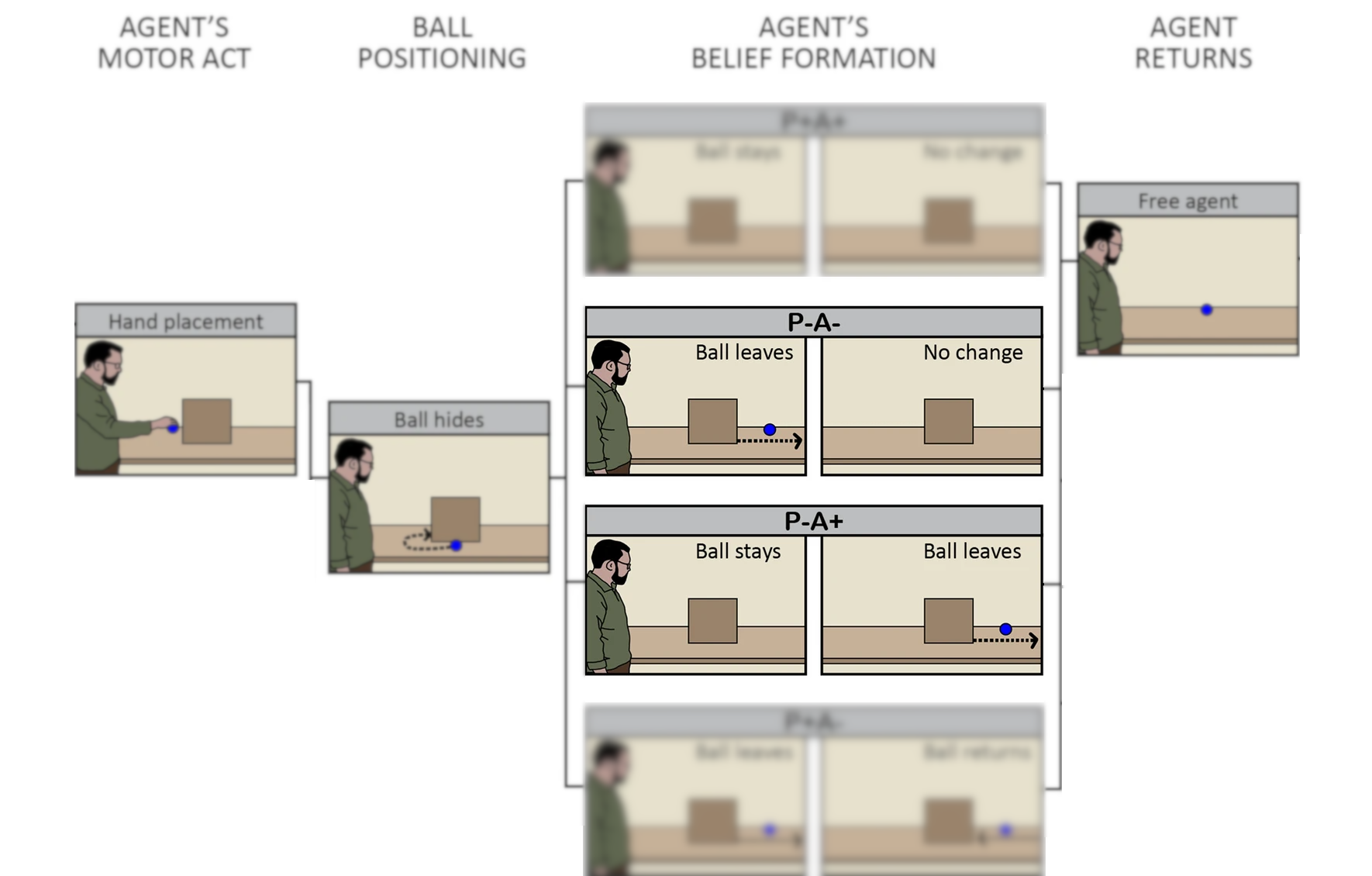

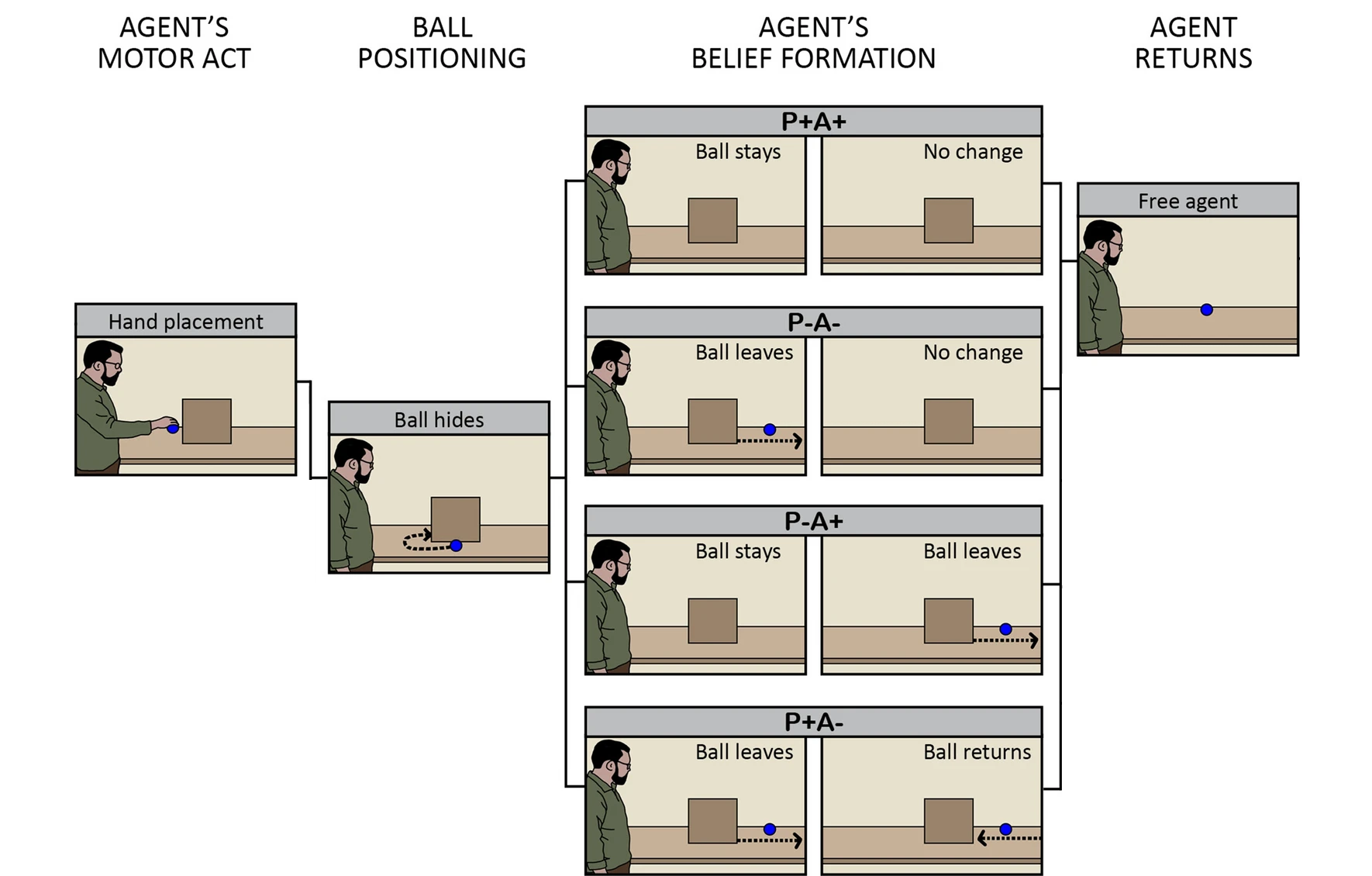

Kovács Effect (Kovács, Téglás, & Endress, 2010)

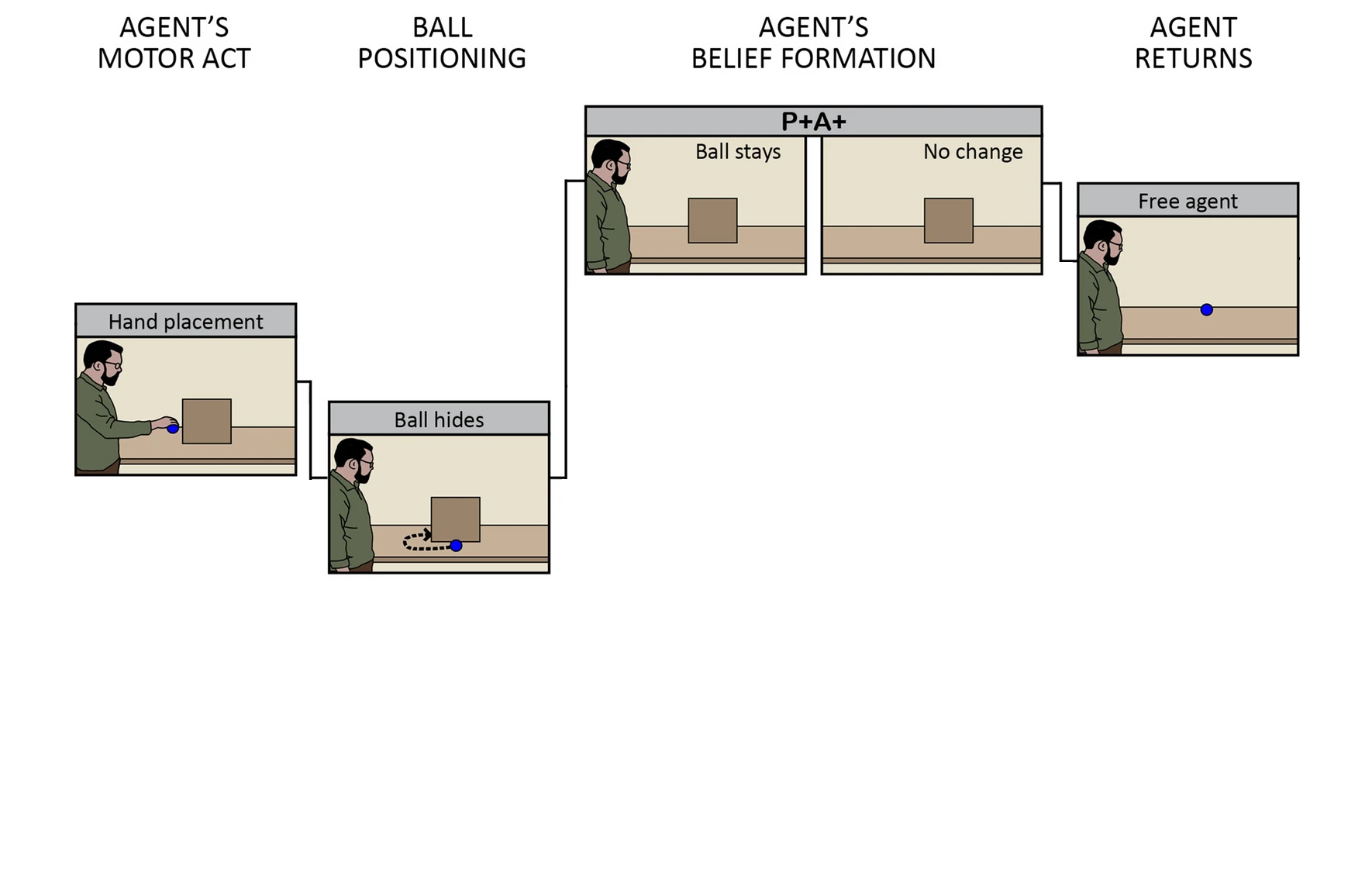

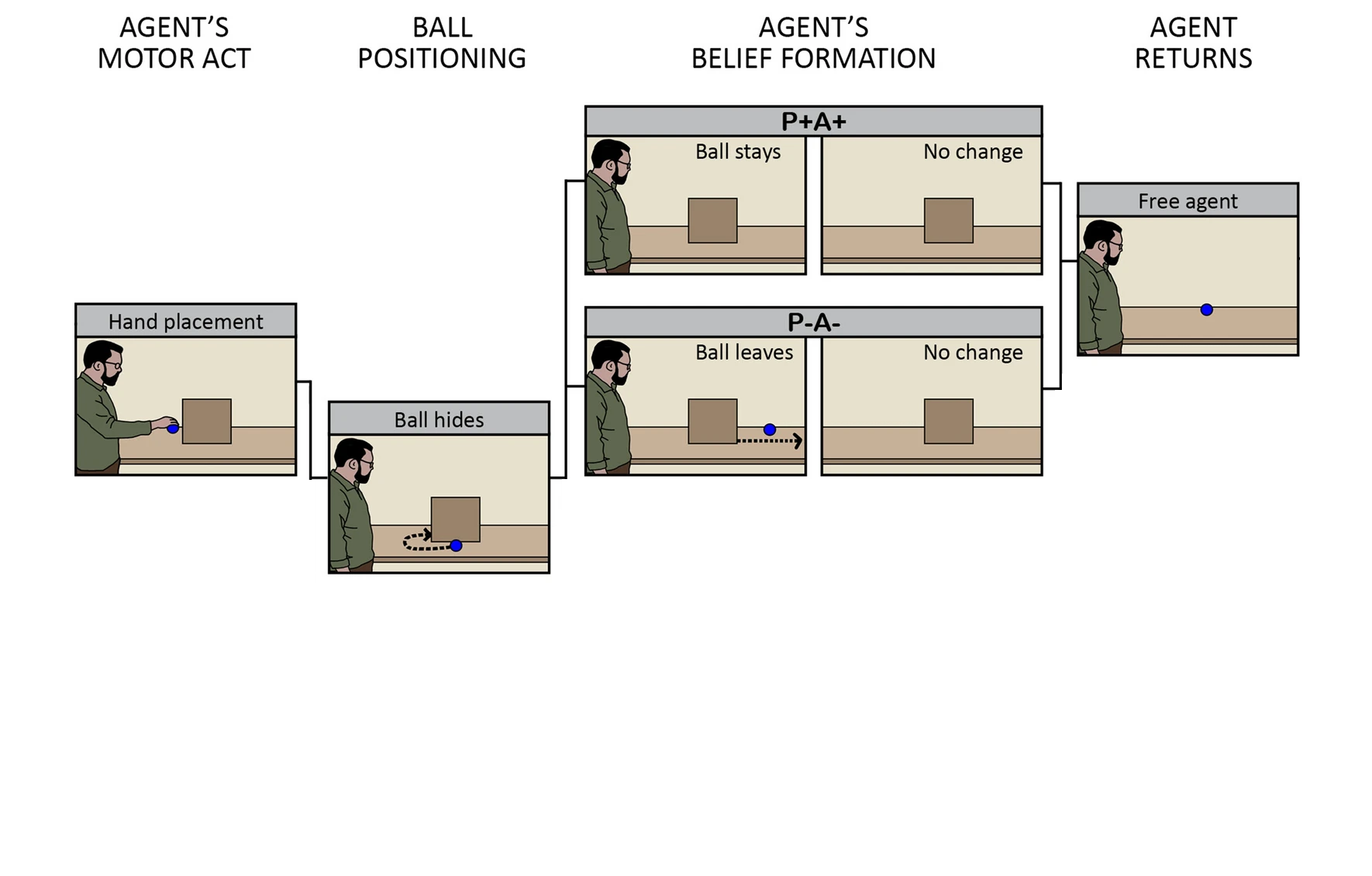

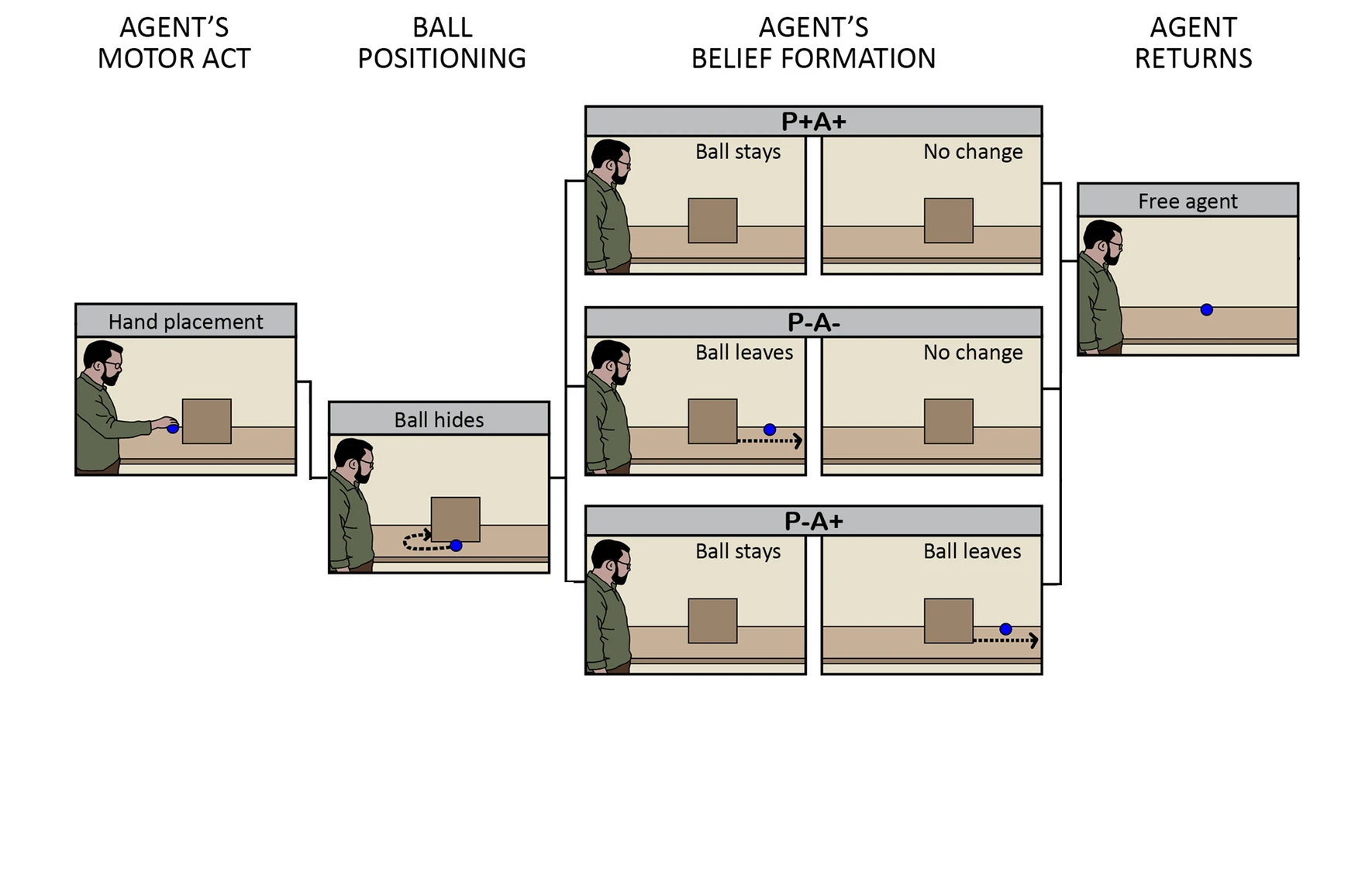

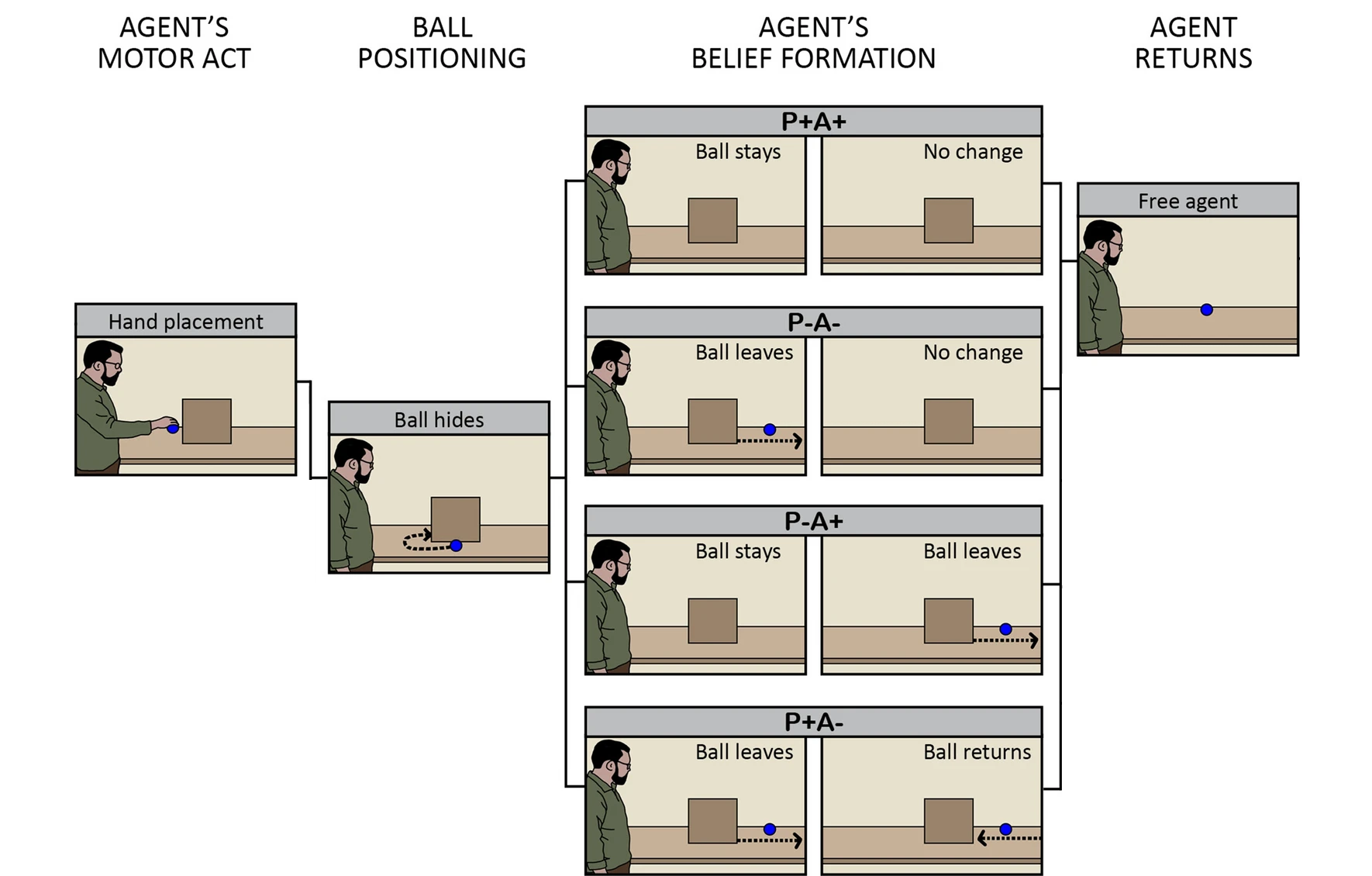

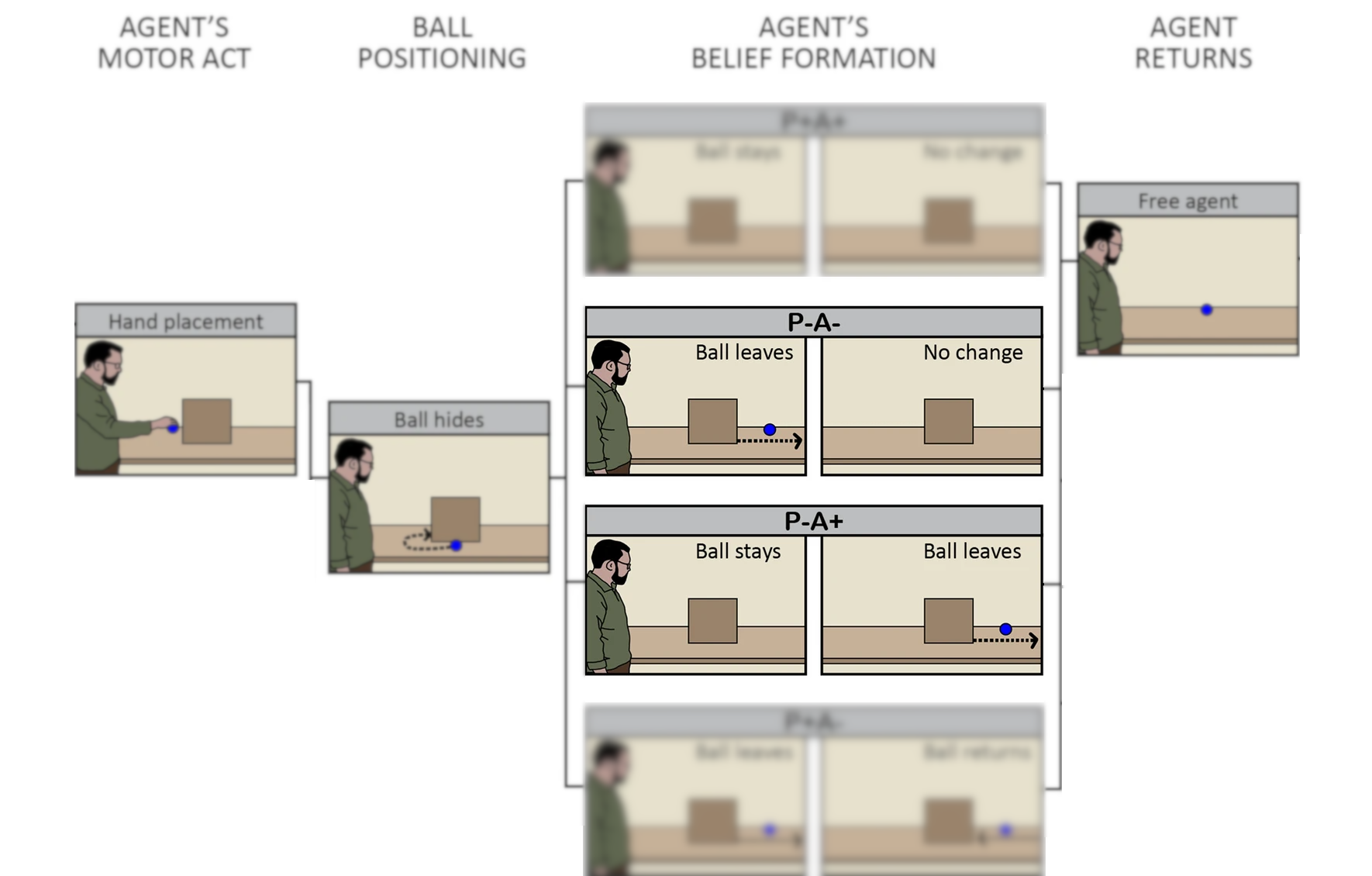

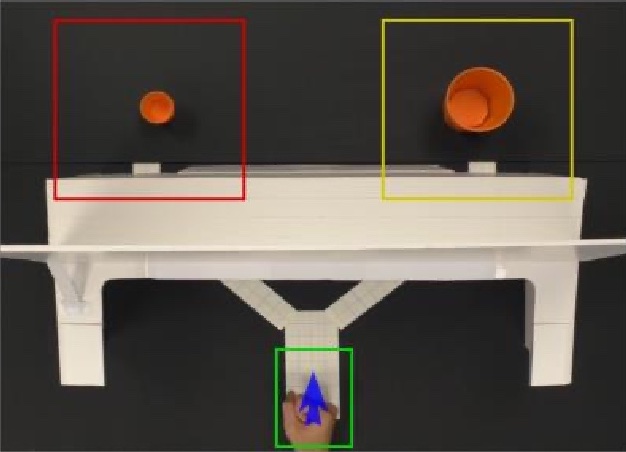

Low, Edwards, & Butterfill (2020, p. figure 1, part) based on Kovács et al. (2010)

Low et al. (2020, p. figure 1, part) based on Kovács et al. (2010)

Low et al. (2020, p. figure 1, part) based on Kovács et al. (2010)

Low et al. (2020, p. figure 1, part) based on Kovács et al. (2010)

Low et al. (2020, p. figure 1, part) based on Kovács et al. (2010)

The Question

Why do others’ false beliefs ever have an effect on your own actions?

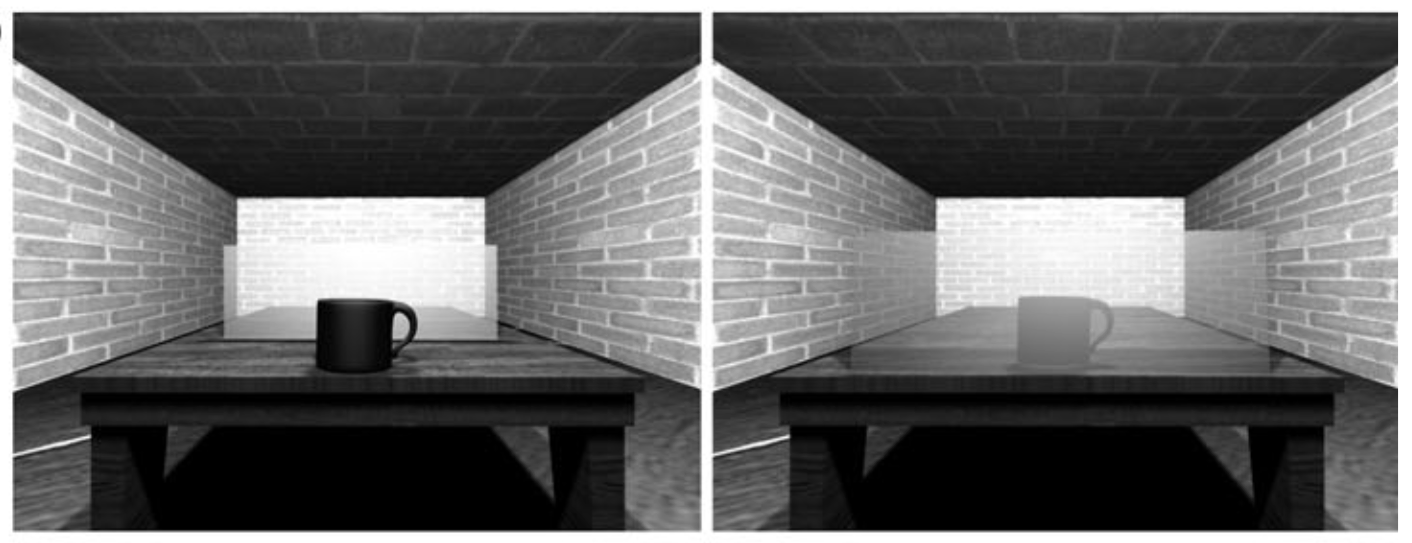

Costantini et al, 2010 figure 1b

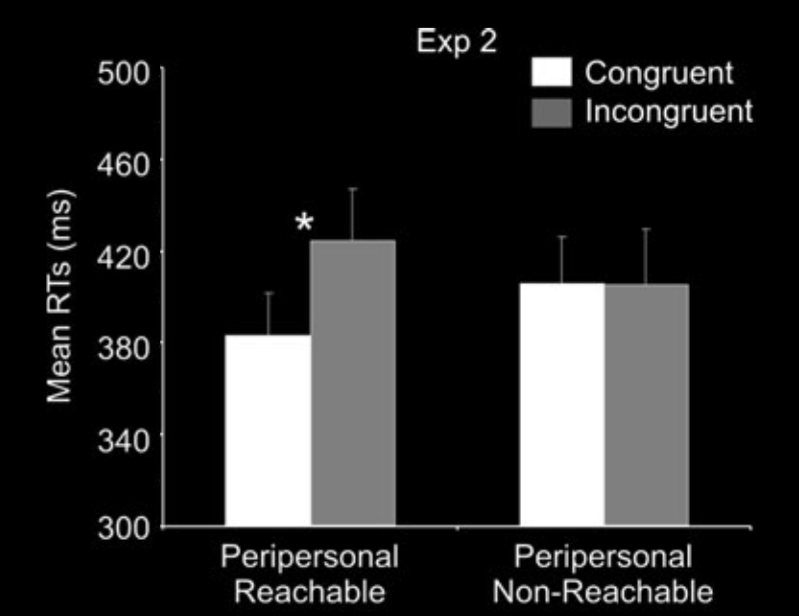

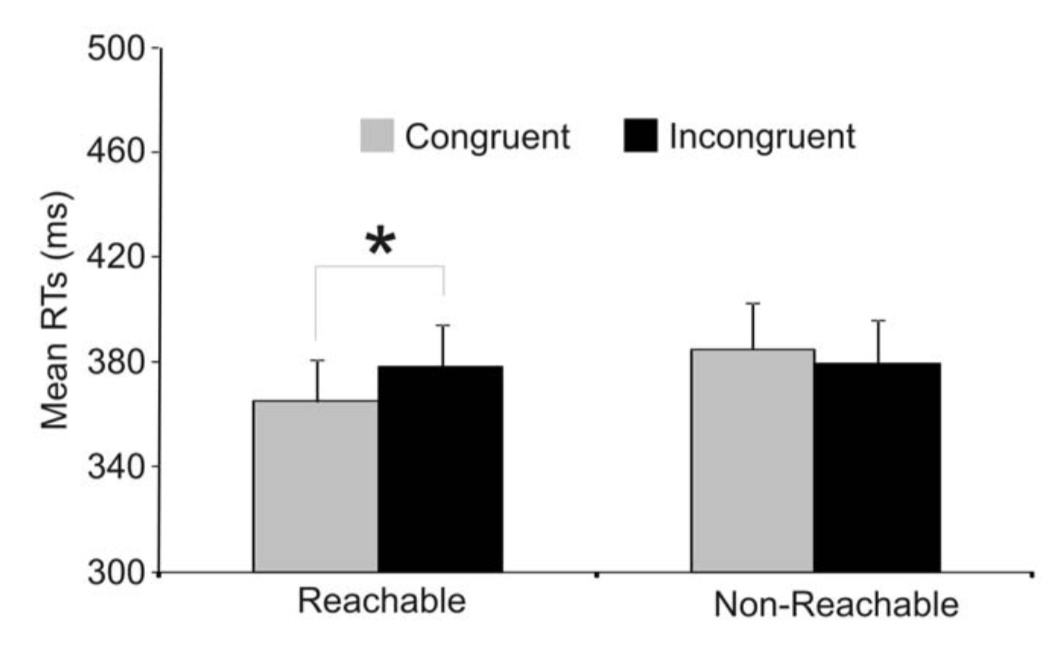

Costantini et al, 2011 figures 3,4

Why do others’ false beliefs ever have an effect on your own actions?

Conjecture: ???

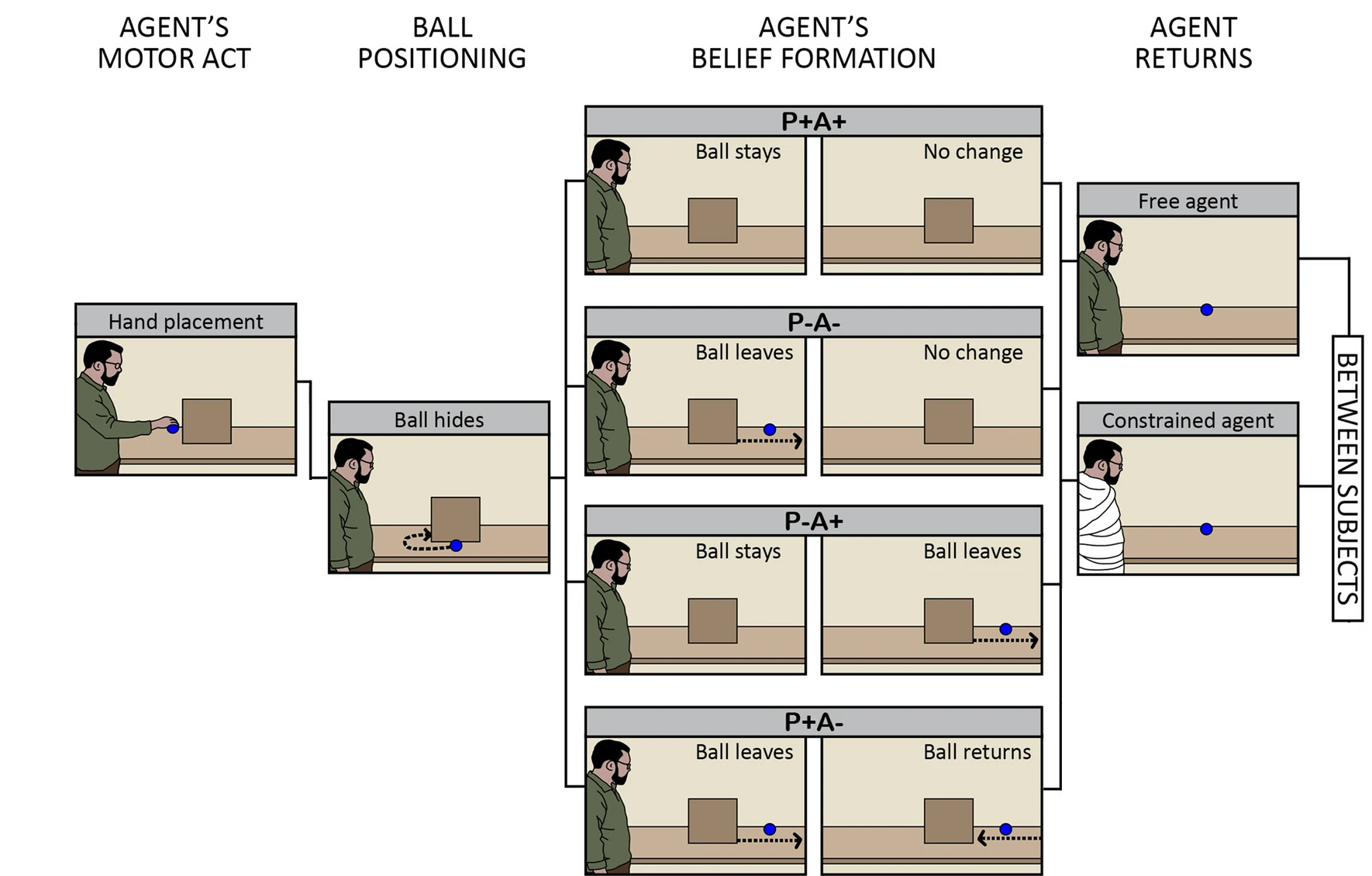

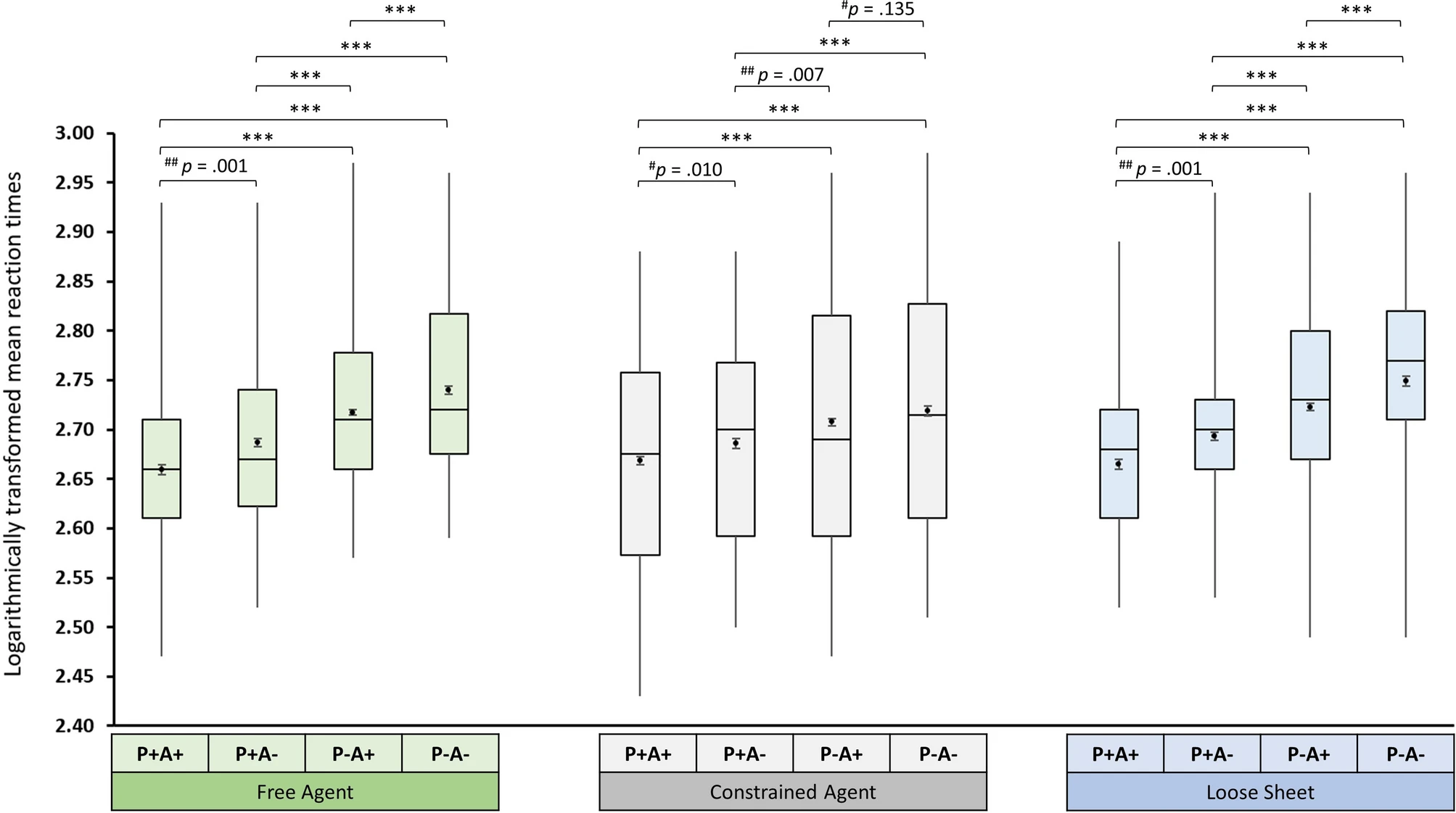

Prediction: constraining others’ action possibilities will reduce task-irrelevant effects of their false beliefs on your reaction times.

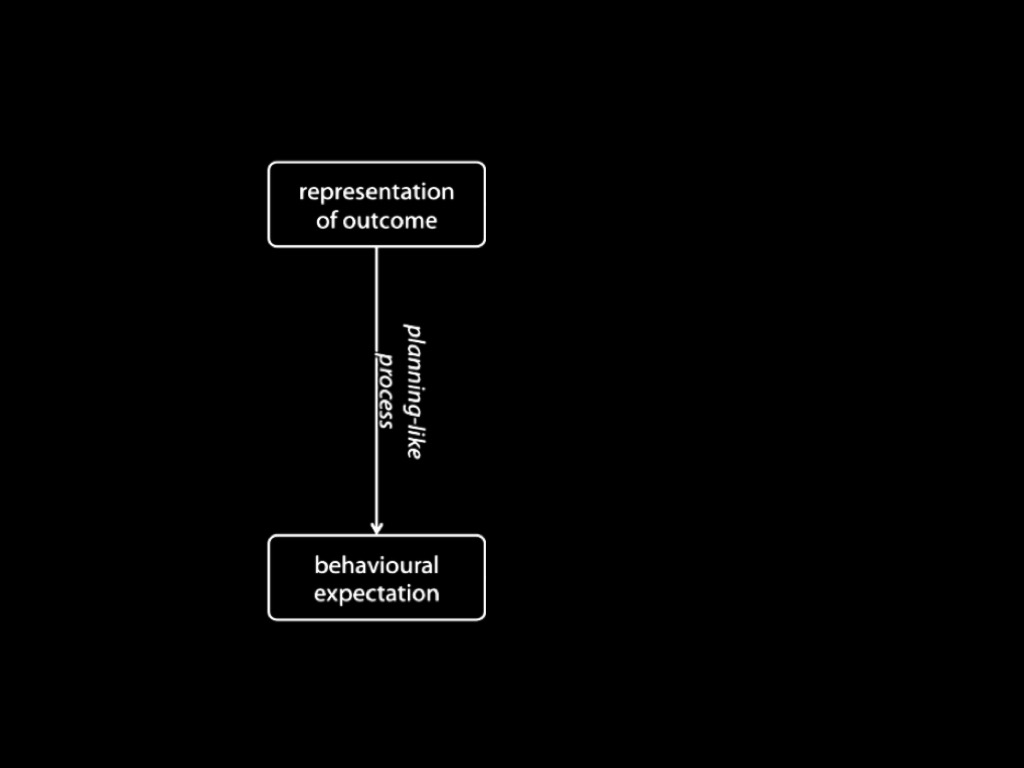

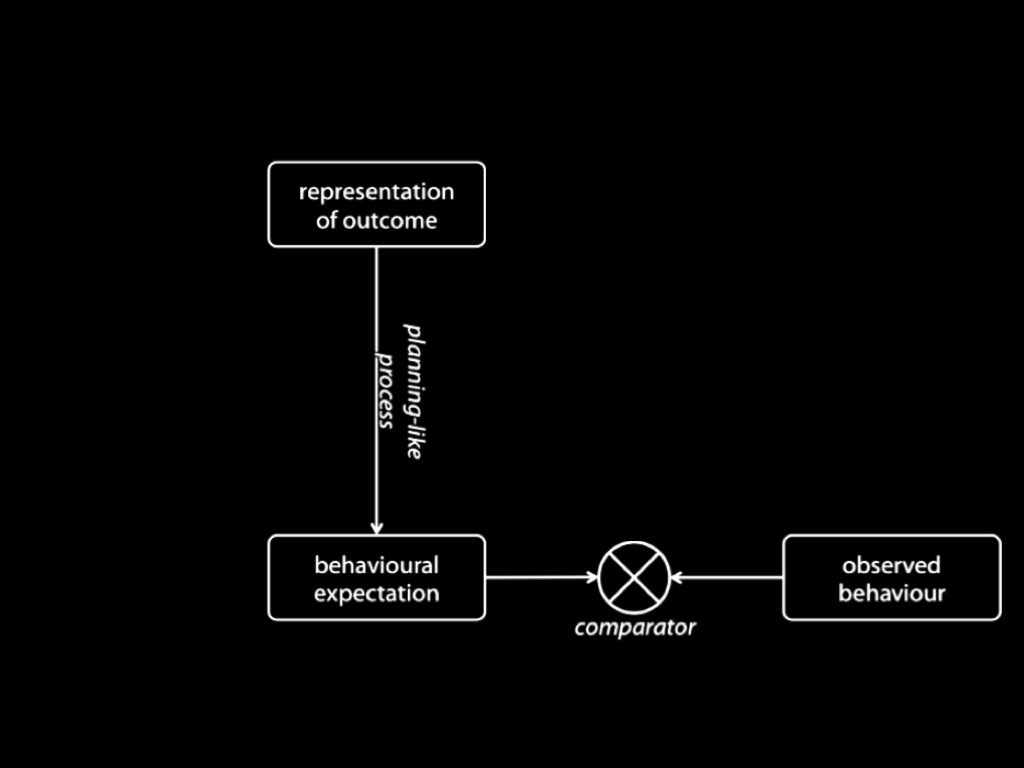

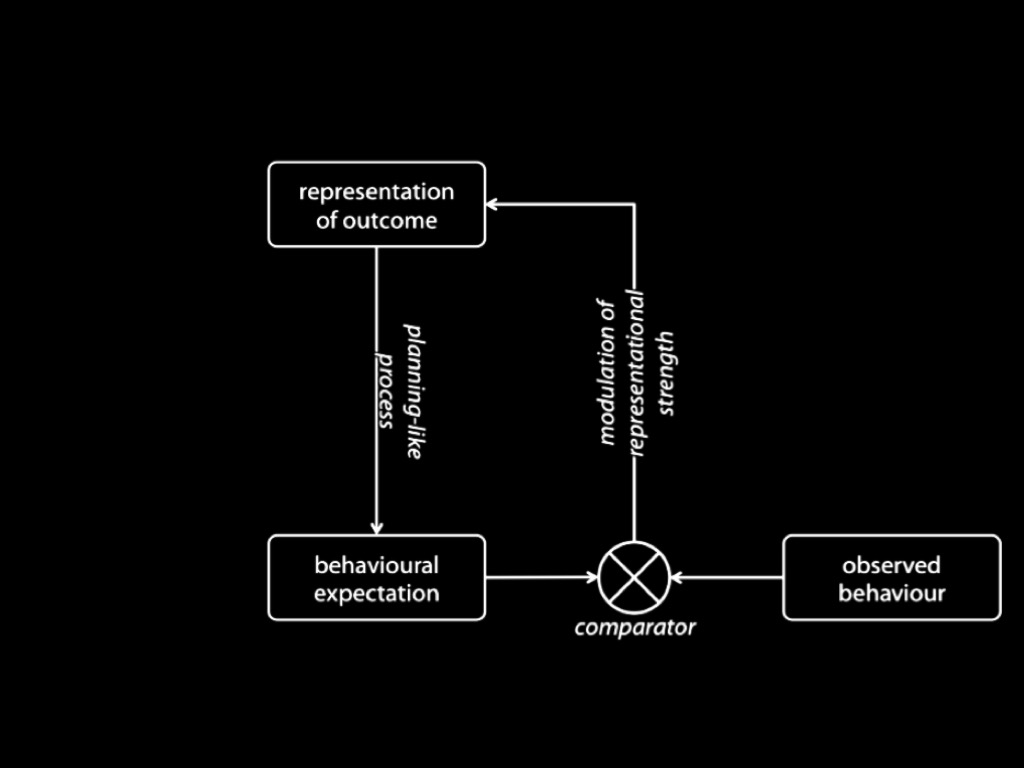

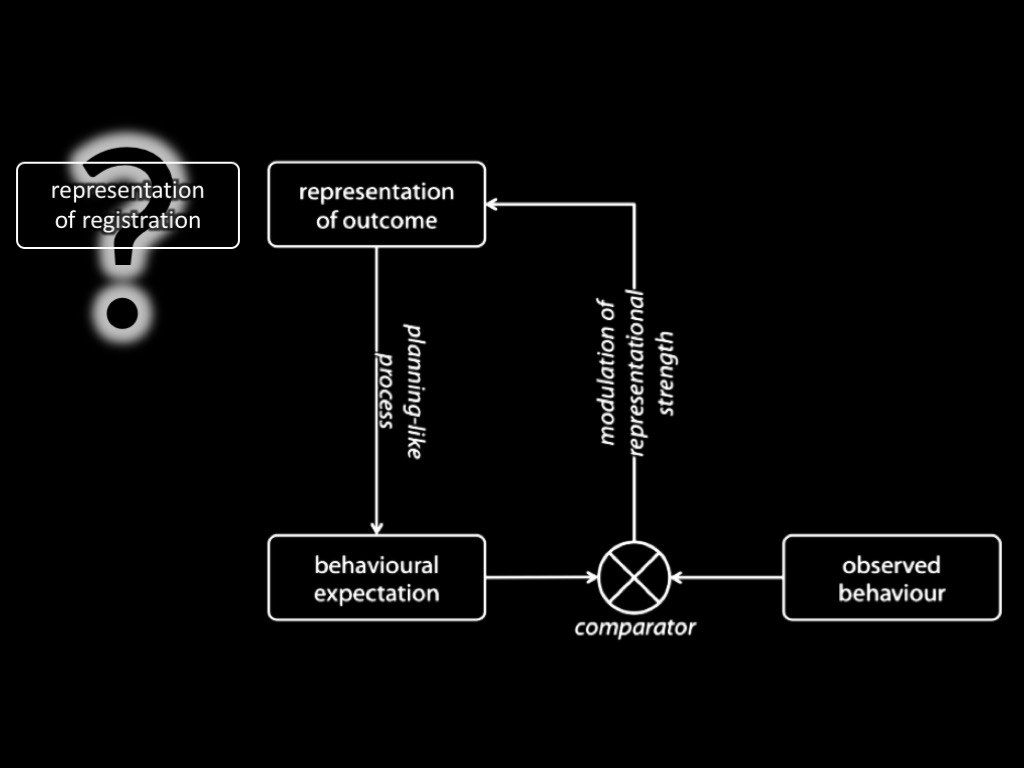

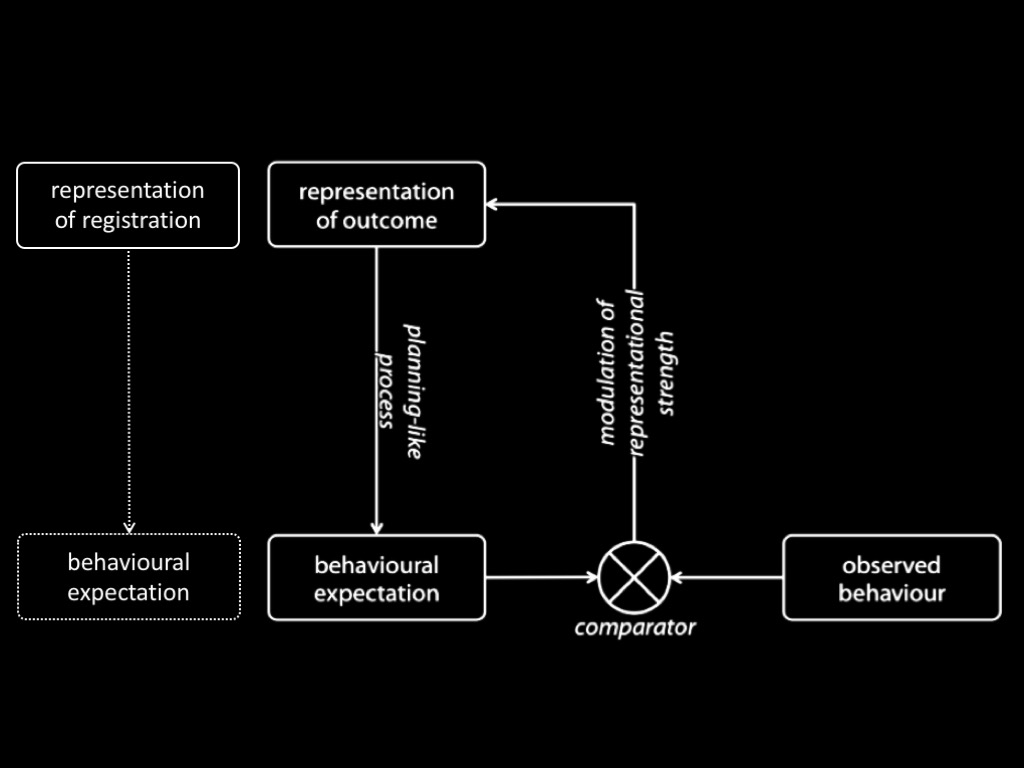

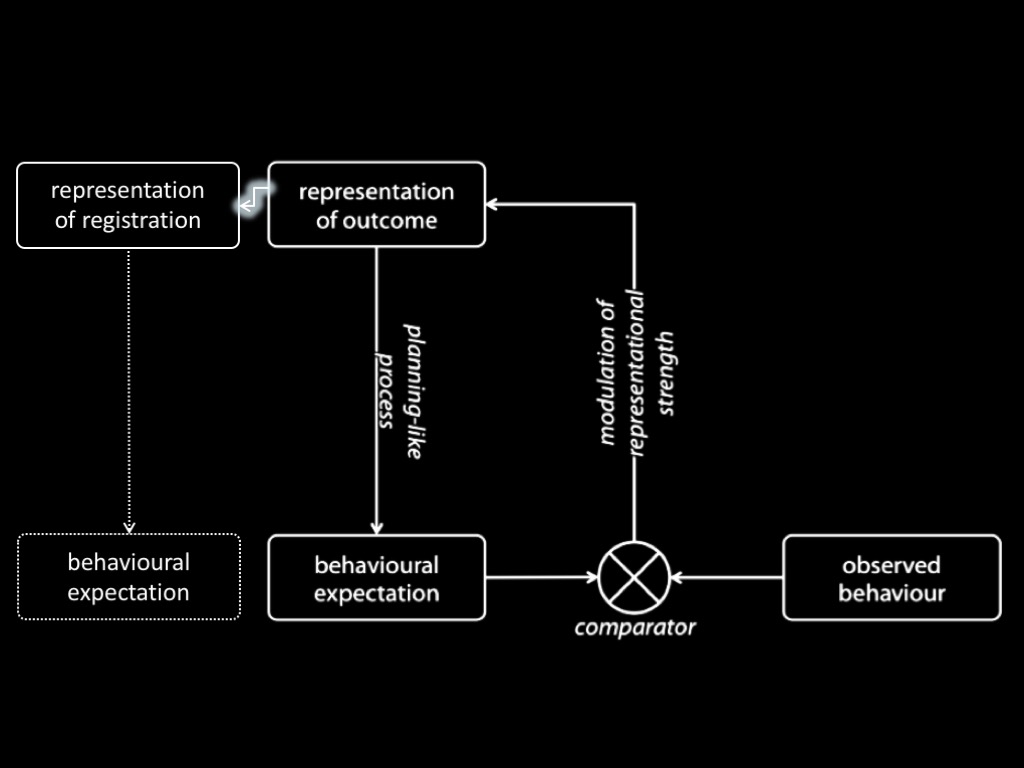

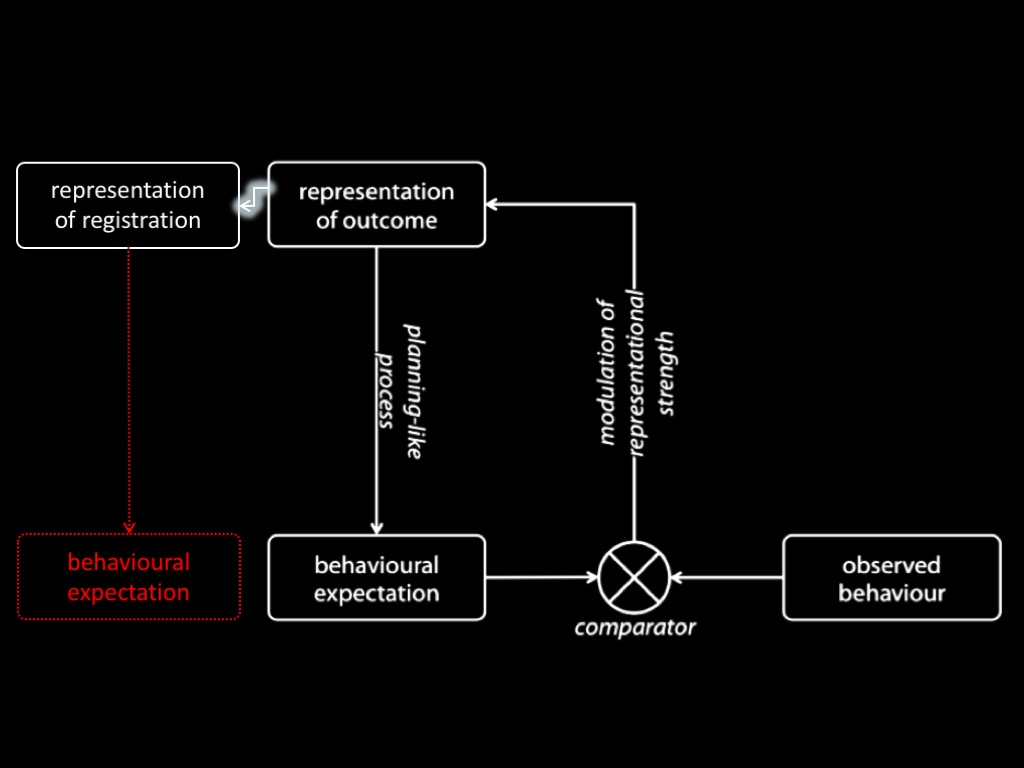

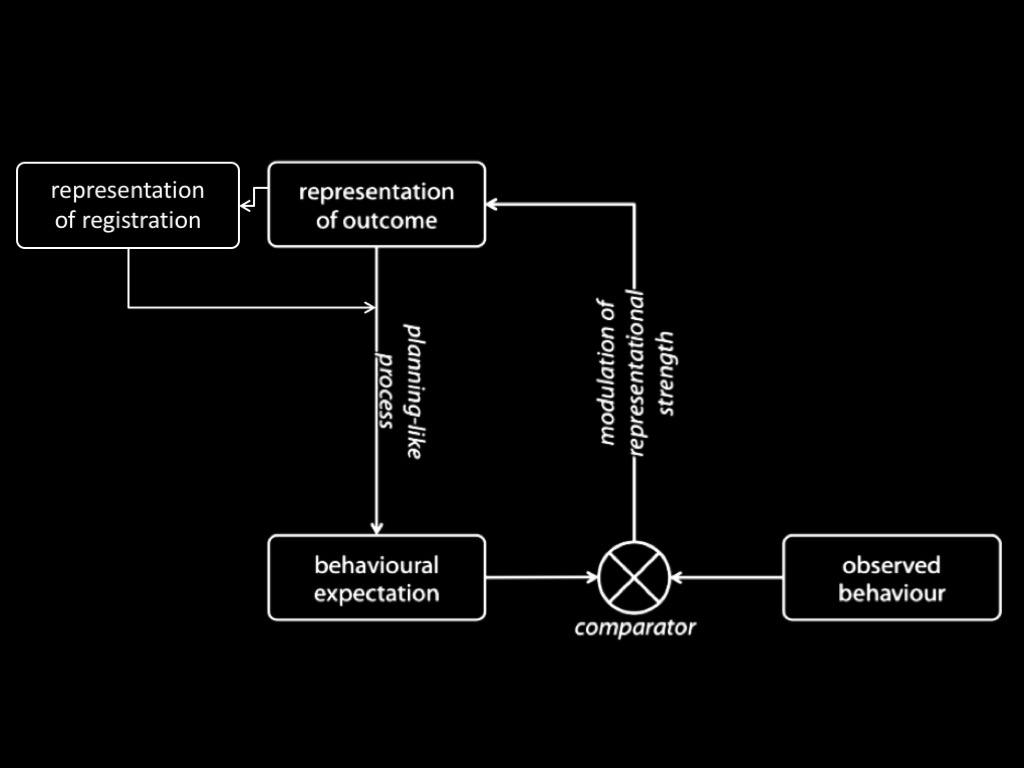

The Model

The Model’s Predictions

1. In motor mindreading only, goal-tracking will manifest sensitivity to agents’ beliefs.

2. In motor mindreading only, physically constraining protagonists (or participants) will impair belief tracking.

Some Evidence

mixed

Low et al. (2020, p. figure 1, part) based on Kovács et al. (2010)

Low et al. (2020, p. figure 1, part) based on Kovács et al. (2010)

Low et al. (2020, p. figure 1, part) based on Kovács et al. (2010)

Low et al. (2020, p. figure 1, part) based on Kovács et al. (2010)

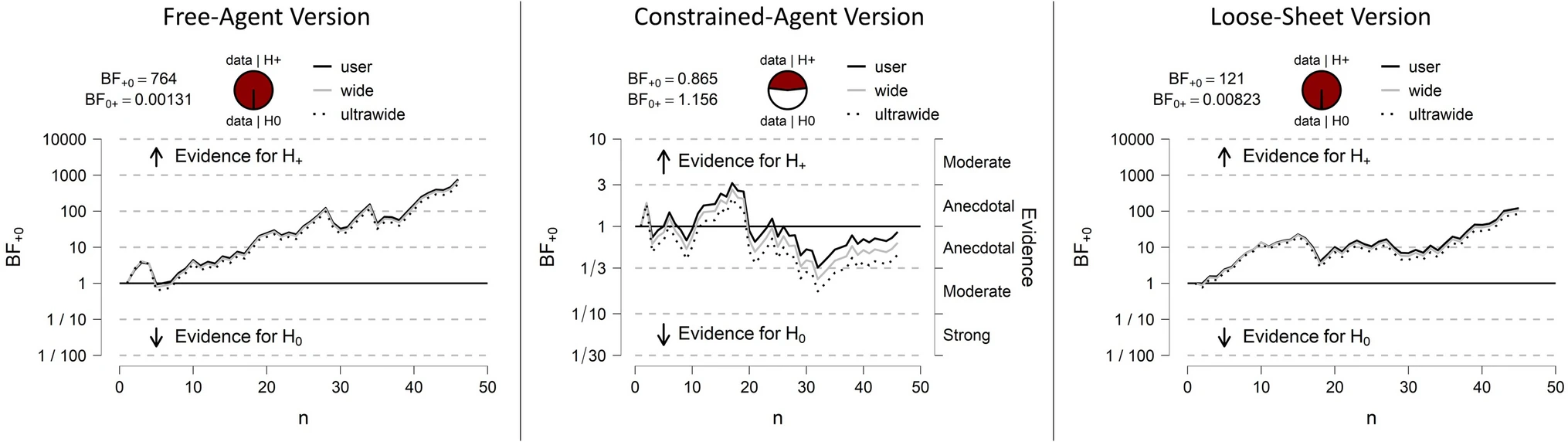

Low et al. (2020, p. figure 2)

Low et al. (2020, p. figure 3)

The Model’s Predictions

1. In motor mindreading only, goal-tracking will manifest sensitivity to agents’ beliefs.

2. In motor mindreading only, physically constraining protagonists (or participants) will impair belief tracking.

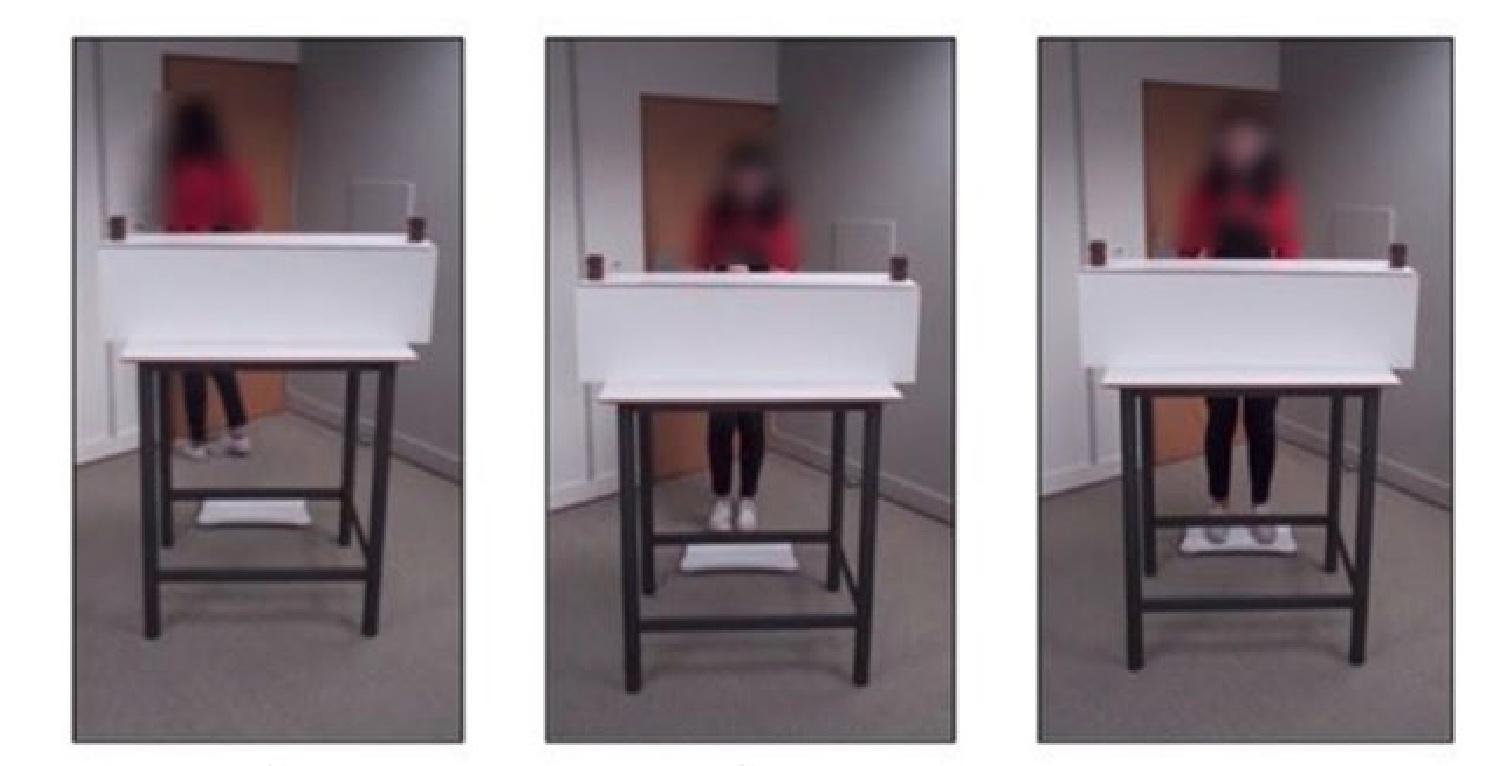

Six (2022, p. figure 11)

The Model’s Predictions

1. In motor mindreading only, goal-tracking will manifest sensitivity to agents’ beliefs.

2. In motor mindreading only, physically constraining protagonists (or participants) will impair belief tracking.

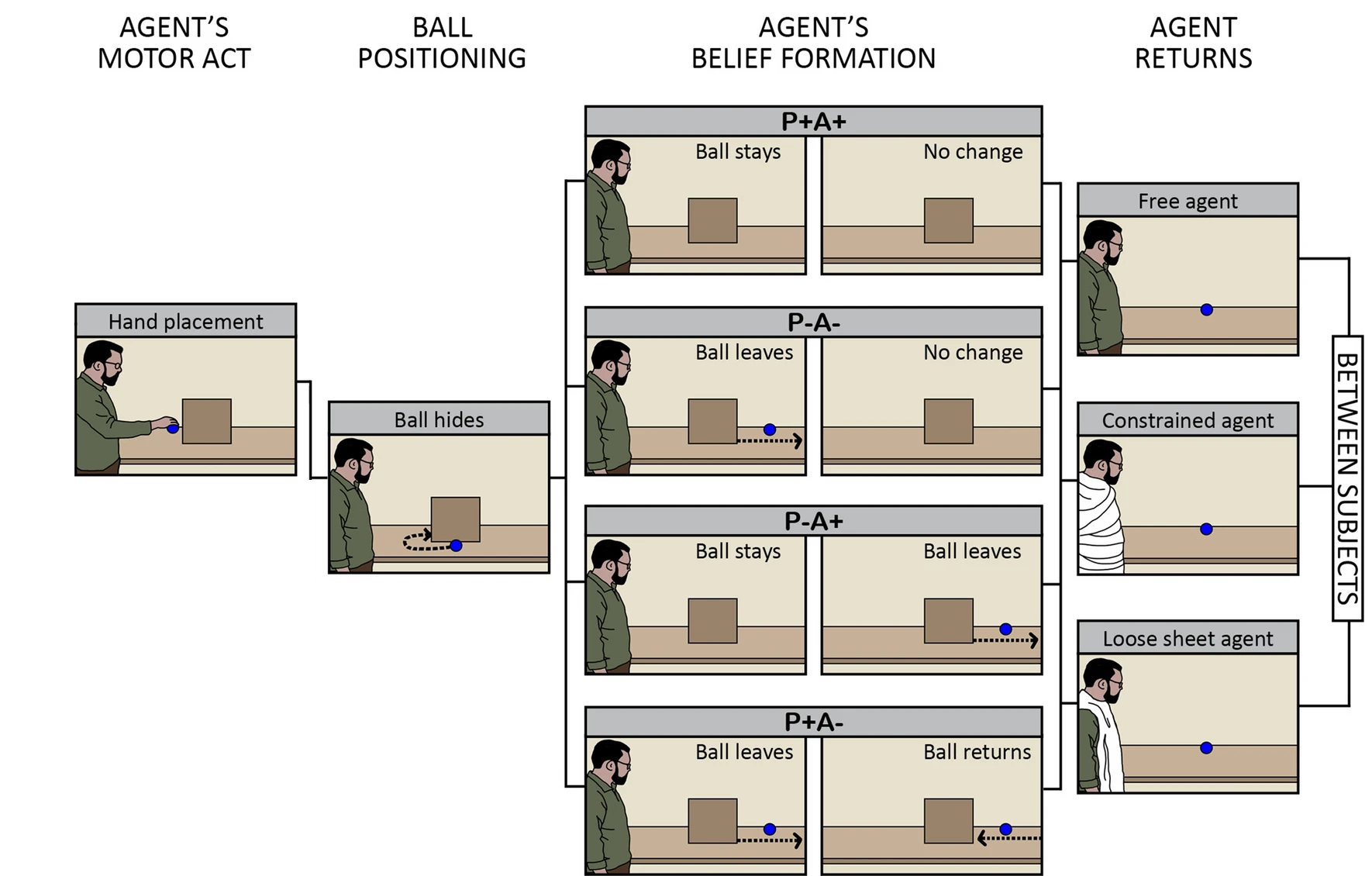

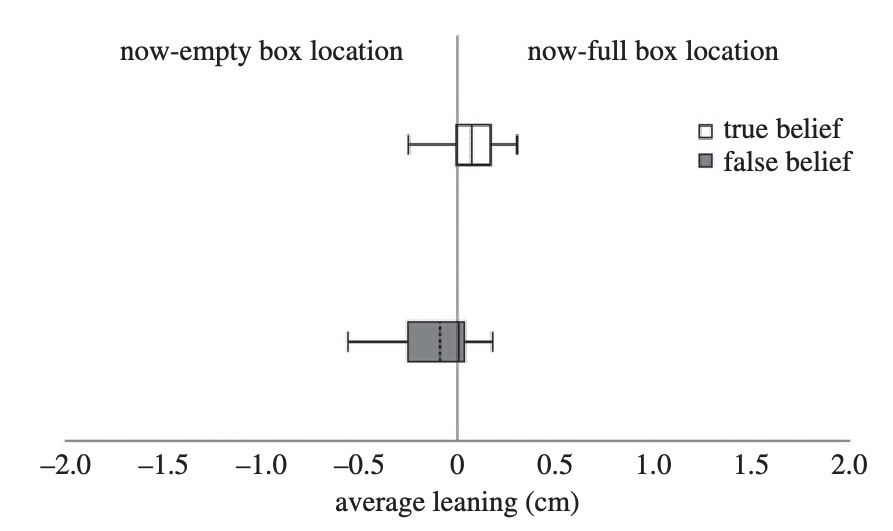

Zani, Butterfill, & Low (2020)

What if we bind the protagonist?

| source | paradigm | measure | who bound? | as predicted? |

| Low &c, 2020 | Kovacs’ Smurf | RT | agent | Y |

| Six, 2022 Exp. 2 | Six’ Cups | looking time | participant | N |

| Zani, forthcoming Exp. 2 | Buttelmann/ helping | leaning | agent | suggestive |

| Sinigaglia, Quarona &c, in prep | Kovacs’ Smurf | RT | agent | unknown |

If there is fast mindreading,

what kind of processes might it involve?

Motor Mindreading?

[email protected] & [email protected]